It’s no longer considered feasible to dedicate time to something that doesn’t guarantee an outcome. A reward, today, is non-negotiable. Life wasn’t this way back when the two machines you see here were India’s heroes. To give you context, in the early 2000s, digital photography wasn’t a thing yet — not for us, anyway. This meant, a succession of photographers would set off on our infamous shoots, going through the rigour of capturing cars and motorcycles on a Nikon F601 or a Contax G1, almost always uncertain of whether or not the photographs would turn out well. Or at all. That’s film photography for you.

Somehow, they always made it work, though. When I proposed, therefore, that Pablo dish out one of his period-correct film cameras for this flashback sequence of a story, I figured we’d all get to live (or re-live, in his case) a moment right from the past. Rounding up the machines was all too simple, too. A couple of calls to well-meaning friends, a clever ambush (for the City), and they showed up at their tidiest best.

POINT OF VIEW

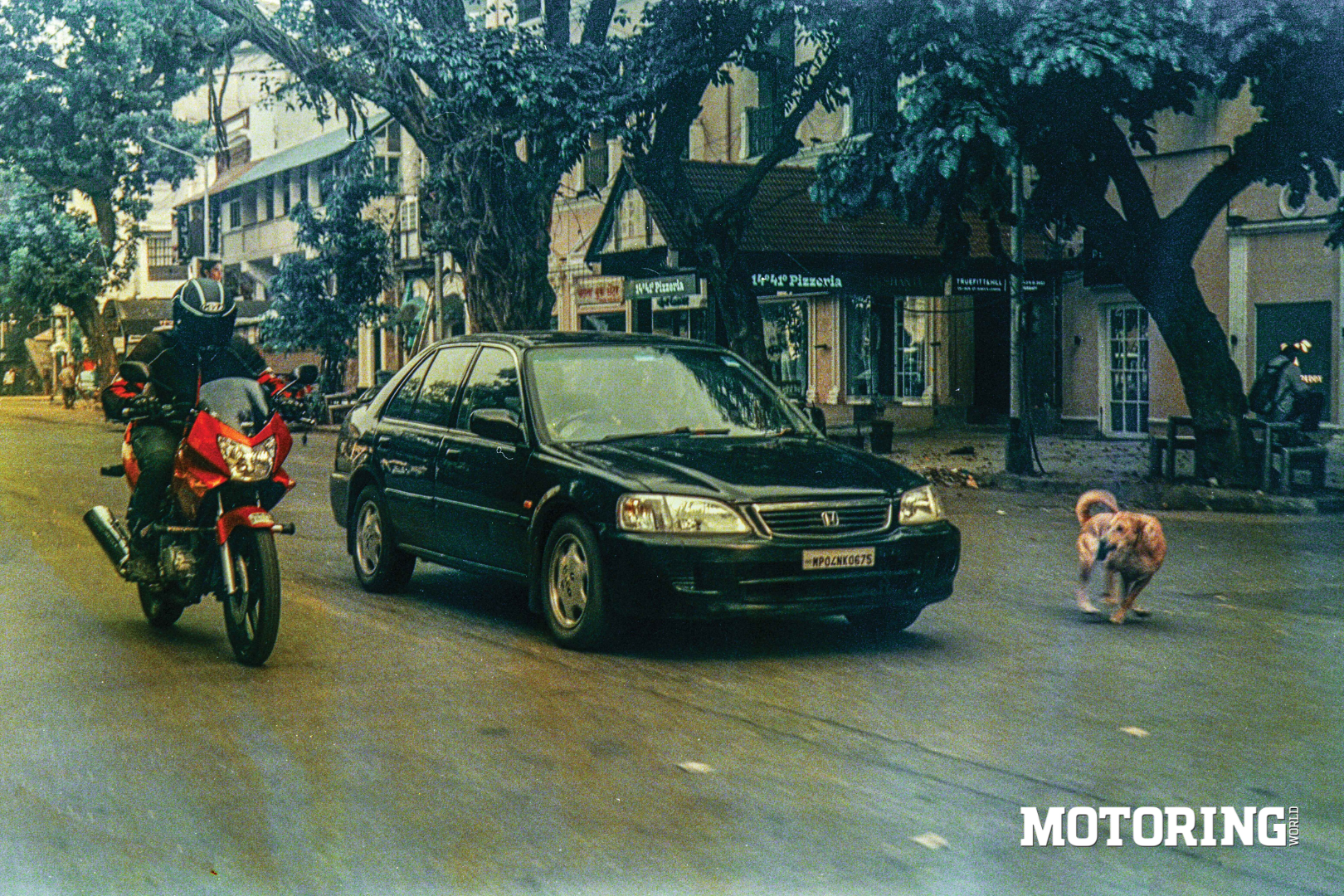

The Honda City VTEC rolled in first, making (thankfully) all the right noises. From its low-slung cabin emerged Miheer Patankar, a dentist, who almost immediately began forewarning us of all of his newly-acquired car’s imperfections. I tried to put him at ease about it, partly because it’s not as if the City has anything to prove today, but also because it couldn’t have been anywhere close to being as disastrous as the City I had bought a few years ago. Mine was probably put together as an experiment — by a biologically inadequate person, at best — and, unsurprisingly, I no longer own it.

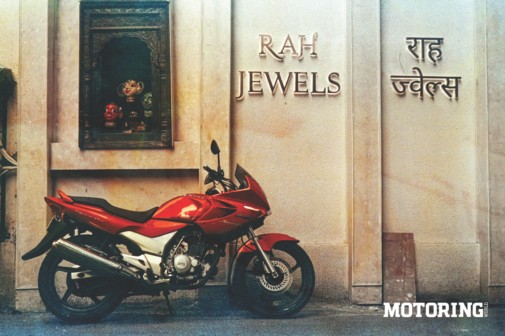

While I struggled with my moment of bittersweet nostalgia, a red blur filled up my peripheral version. It was the Hero Honda Karizma, the erstwhile poster boy of India’s four-stroke performance-bike era. This particular example had only recently emerged from a restoration and its owner, Prem Miskin, excitedly told us all about it.

Understandably, then, I was raring to have a go at this pair. It’s not every day that you get to erase the last 20 years of your life, right? Except, of course, it was Pablo who first had to have a go at them with his Yashica FX-3 Super 2000 camera to which, in an impressive show of dexterity, he began to attach lots of paraphernalia. The last of these bits was, of course, a roll of Kodak Vision 250D.

DEPTH OF FIELD

This compact reel, Pablo explained, would allow us exactly 36 frames to capture the day’s action. He did mention having another one tucked away as a reserve, although I understood using it would dial in some kind of photographer’s remorse. Imagine the embarrassment in using a new roll of film just to shoot a handful of additional shots! That aside, the process of setting up the camera and the roll was a wonderfully mechanical one — I am certain it was a lot tougher than he made it look, honestly — involving careful insertion of the reel into a sprocketed roller and pulling a trigger-like lever while lifting his left foot over his head. Okay, I made up the last bit.

About 13 years had passed before Pablo was finally ready to shoot. ‘Okay, I have exactly 36 frames to get this right,’ he said with visible concern, ‘So I have to really think before taking a shot.’ I don’t think I have conveyed the gravity of that statement to its full impact, so here’s some context. On a film camera, there’s obviously no way to instantly verify whether or not you’ve nailed a shot — there’s no screen and no plug-and-play memory card either. This means you only learn about what you’ve shot after a man who lives in a dark room tells you how well or poorly you’ve done. And that’s, usually, a couple of days later. Being sure — of the light, the composition, of any background clutter — is, therefore, extremely critical and, even after all that, it still is greatly a matter of luck!

I’m, at best, a rookie at photography, but I couldn’t help noticing the practised, fluid choreography of what Pablo was up to. You know how the experts always make difficult things look comically easy, no? It was exactly that. Good old composition, dictated by thought, preparation and immense observation. As any good photographer will tell you, composition is to photography what character is to a man; it’s everything. Hyper-realism and retina-piercing sharpness can, simply, never outdo a neatly framed shot. The 35 frames that followed were, unsurprisingly, pure poetry.

CLOSE UP

Over the course of the shoot, more poetry followed. This time, the kind fuelled by internal combustion. Miheer was unconcerned about letting me drive his VTEC, so I more or less dropped into the driver’s seat in an instant. Going by early impressions, my muscle memory seemed to be in for a treat, adapting very quickly to the low seating, with my tailbone seemingly grazing the tarmac beneath.

The City’s interior is all ‘function’ — there’s no screen in there other than a dot matrix clock insert on the dash, and another one on the aftermarket Pioneer head unit — and just very intuitive. As a driver, everything was precisely where I’d have wanted it to be. For my overgrown dimensions, it was still a comfortable-enough interior and I don’t think I concealed my excitement about being let loose in one very well.

FOCUS

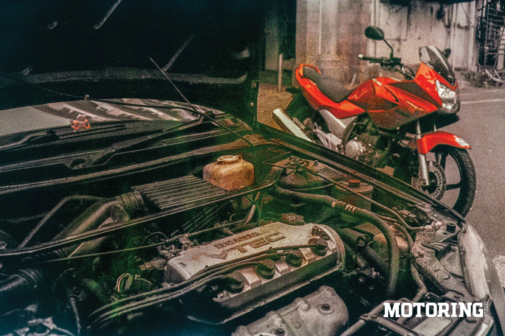

The City VTEC is exactly all of the things it was, in its day — light, stylish and, most notably, fast. It’s a 106-bhp sedan and it features Honda’s variable valve timing and lift electronic control system (how that abbreviates to VTEC, I don’t know), a feature seen on legends like the S2000 and the NSX! Back in the day, it was slower than only a couple of top-flight Mercs, but significantly quicker than its competition (Ikon, Baleno, Astra, Siena) by anywhere between two and five whole seconds! Although I didn’t attempt it, the VTEC is capable of going from 0 to 100 kph in a shade over 10 seconds — and that, too, because it requires a silly shift up to third at 98 kph, if I remember the article I’d read about it in Overdrive magazine’s ‘0-100-0’ special issue correctly.

I had no notions of attempting any such feats, of course. Instead, I drove it around gently, only allowing myself a couple of short bursts of speed, which gave away its intent and capability all too easily. Once a fast car, always a fast car, right? In any case, what made the VTEC such a rage was that all of its power was extremely accessible. The SOHC mill revved freely and then, once you hit 5000 rpm, the VTEC surge would propel you into very committed acceleration. Yes, this is a Honda family sedan we’re talking about — can you believe it? I love it, not only for its performance but, more importantly, for what it represented in a largely regressive automotive universe back in the early 2000s.

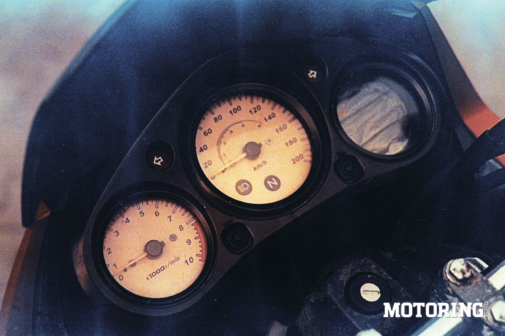

The Karizma was a similarly progressive number. It had one job — to steal the Pulsar 180’s limelight forever — and it sure made a seriously credible attempt on most counts. While the Pulsar was all about frantic speed, the Karizma was about being faster but calmer. Indeed, its CRF230- based engine relied more on its rich spread of torque than on its 17-bhp output. It was composed, vastly more refined (than the P180, that is) and then there was the small matter of how good it looked. A quarter-faired 223cc motorcycle with alloy wheels was a huge deal back in the summer of 2003!

On sheer performance, it didn’t feel too out of touch in 2024 either. Seeing how much our motorcycles have evolved since the arrival of the Karizma, I’m surprised to say it still feels comfortably fast. It’s been years since I rode a Karizma but, by the time I had hit second gear, I was already perfectly at home in its plush seat, almost immediately doing the kind of things with it that I did back when it hadn’t become a shadow of itself. It was always an encouraging, forgiving sort of bike, primarily down to its friendly power delivery and composure, and I was happy to be reacquainting myself with it.

Unlike the City, though, the Karizma wasn’t so much a product of engineering advancements — it was more a masterstroke of configuration, if at all. So, while Honda pulled off a shocker in 2004 by completely rewriting the code for the City (purists tend to be less polite about it), the Karizma continued virtually unchanged for well over a decade since its launch. Curiously, the performance benchmarks of the era in, both, the two and four wheeled worlds, were powered by Honda engines. We clearly live in a wildly different era today.

This is what happens, I suppose, when the appetite for a reward outweighs everything you stand for. It gets in the way! To be fair, conformity has become more a matter of survival than of mere appeasement, so it’s only obvious that we aren’t going to have affordable family sedans setting performance benchmarks anymore, for one. On the bright side, though, we live around some very exciting machines today, quite a lot of them still within reach. And if nostalgia is anything to go by, the future isn’t going to be a bad place at all.