The beginnings and ends of some stories are the same. Or at least, the beginning of a car and the end of another one, in this case — the Honda Brio you see here once rearended the Maruti Suzuki Esteem, and that’s the reason why they are what they are today. You see, two friends, Ashad Pasha in the Esteem and Ismail Khan in the Brio were heading to the Hampi Autocross in 2020, when on a single-lane road a sudden speed breaker caused the former to brake hard and the latter couldn’t do the same. I suspect they’re quite the optimists, since they made the most of that particular misfortune and turned these cars into more than they were meant to be.

It wasn’t what Pasha had imagined when his rearview mirror was filling up with the Brio, though, especially given that it was his mother’s car that was bearing down on him. I bet he invoked that most revered prayer of sons everywhere: ‘It wasn’t me!’ Now, how many of us got 130 bhp as an outcome of that situation? Lucky guy. Since the Brio’s front end was a write-off, Pasha thought what any normal person would: ‘I wonder if a more powerful engine will fit into this space’.

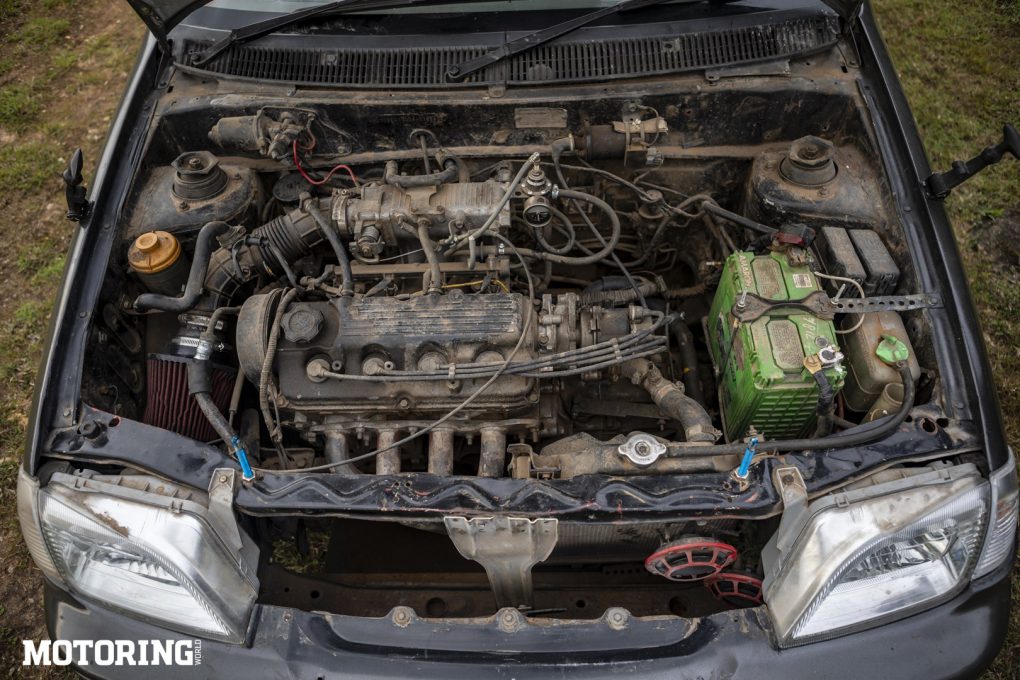

And he didn’t have to look far; the Honda City’s 1.5-litre unit was a straight fit, this one from a 2013 model, and that’s why I choose to call it Bigheart. Still, obviously, that wasn’t enough. So, in went an aftermarket air filter, an engine remap, an RDP racing exhaust, Brembo brake rotors, and 15-inch wheels with Yokohama tyres. End result? Said 130 bhp and a 0-100 kph time of under 10 seconds. Mom must be proud. Or at least we all hope so.

The Esteem, a venerable motorsport staple in India, got what any self-respecting autocross setup deserves. First of all, there’s the very obvious roll cage (sorry, mom); fibreglass rear doors, bonnet and boot; suitably stiffer suspension not suitable for your average commute; increased compression, a high-lift cam, ported and polished heads, an ECU remap, an XCD stage 1 clutch, and a close-ratio gearbox. Basically, what the rules allow and your neighbourhood RTO grudgingly accepts. Maybe.

Nonetheless, I doubt anyone would dislike the Brio’s mutedbut-soulful hum when it fires up. Frankly, it’s how every car should sound, even over the Esteem’s mad internal-combustion shrieks. The Brio made a sound that Mr Honda would smile at in his driveway, never mind the factory. Given that it was still an older-gen Honda, a modded one at that, every blip of the throttle was a silky burst of progress, and each one fooled me into thinking I was slower than I was. I wasn’t. I put my right foot hard into a tub of honey and was rewarded with two front wheels spinning, that exhaust singing like said honey, and my hands content to hold the steering wheel even if I drove that sweet symphony into a wall with a smile on my face. Stupid? You bet.

Overall impression? This Brio lives in Karnataka; there’s a similar blue Brio in my colony in Mumbai that I’ve walked past so many times since, have always looked at, and remembered the other one. I couldn’t not have, that’s the impression that car made on me. The Esteem? Well. Let’s just say its name will challenge your own psychological namesake. Like any true motorsport machine, an uncertain idling rhythm turned into a full-blown roar past halfthrottle, as it should. There was no interior to speak of, everything was stripped and offered to the ghosts of weight reduction. The orange metal tubing was almost breathing down my neck, adding more than a sense of occasion; it felt like an austere chamber for a speed monk.

Seeing Pasha nonchalantly slide the Esteem past the Brio, I wondered if the original incident might repeat itself. Obviously, I need not have worried, since he was actually nonchalant, almost looking bored as he pulled four-wheel slides mere metres from us. Perhaps that’s his camera face, I didn’t ask. Then again, when I drove the Esteem, my face was probably a more expressive one because the six-point harness was tight enough to turn me a few shades purpler. Even then, it was apparent even to me that the Esteem’s setup is built for total control.

I can’t imagine why Honda didn’t make a Brio like this one, or why Maruti didn’t, either. Especially the latter, since there are thousands of motorsport enthusiasts who’d love to have a manufacturer supply them with reliable parts. Sure, there might be more to it than that, but I can’t imagine what it is other than numbers. For the empire of Maruti, a tiny village of racers matters not. And as great as the Esteem naturally is, it’s the Brio that smiles brightest, a family hatch befitting a motorsport household. And no one can say that nothing good ever came from a speed breaker.