Moments. For once, that’s what a trip is about. There’s no linear recollection of what’s happened during these few days. Instead, fragments of the journey stray into my mind, washed over with the tinge of improbability that’s always brought on by retrospection. ‘Did it really happen?’ ‘Was I really there?’ ‘Is there anything more terrible on this planet than the drive from Delhi to Mussoorie?’ However, all along the way, I see schoolchildren of all shapes and sizes, ostensibly in transit between places of learning and residence. I don’t know why yet, but it’s a sight that always fills me with hope for the future. I wonder how many of them know of Ruskin Bond; I used to read him in school textbooks a long time ago and here I am on my way to meet him. And in the same mental breath I hope Mussoorie, where he lives, doesn’t disappoint.

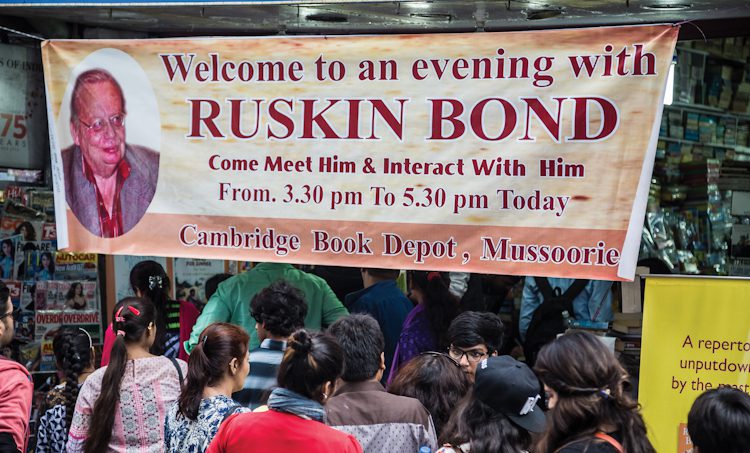

Driving back and into Mussoorie, we get stuck in the worst traffic jam I’ve ever seen. We’re headed to Cambridge Book Depot on Mall Road which Bond visits every Saturday to interact with his fans. We’re to get there 45 minutes before Bond actually starts meeting people, so that we can have a quiet word with him. But the extremely narrow road (I’d think thrice before calling it even a lane) has two-way traffic backed up all the way up and down the mountain. The cool mountain air I was gratefully taking in all day is now replaced with the smell of clutches cooking themselves into a traffic-jam buffet. Ruman and Harshit jump out and direct me through gaps that are narrower than the A3’s shutlines. Some well-meaning Samaritans try to give additional directions, but they seem not to understand that a pair of eyes cannot follow 16 hands at once. After what seems like an age, we finally reach Cambridge, only to see a long line of people already staking claim to Bond’s time. Looks like we have a lot of time to murder slowly.

DID YOU KNOW?

- Mussoorie has more than 14 points of interest which include waterfalls, lakes, gardens, temples and so on. Enough to keep a tourist busy.

- Mussoorie is also home to the remains of Sir George Everest’s house. He’s the one after whom Mt Everest is named.

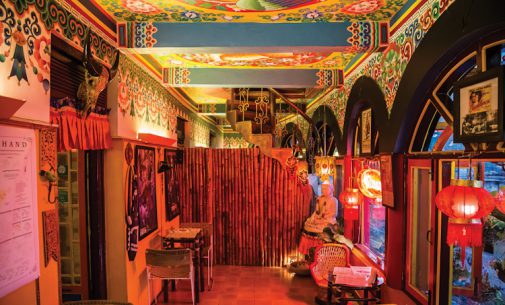

I walk into Cambridge, even as two loud ladies are making a nuisance of themselves, arguing with the gentleman at the counter about why they weren’t told earlier that Bond was leaving so that they wouldn’t waste their time standing in line. I really don’t know where this strong sense of entitlement comes from. Inside the shop, there is a quiet little boy being convinced by an exceptionally loud father to buy one book over the other because it’s cheaper. I hastily pick up a few books for myself and friends, pay the harassed gentleman at the counter and leave before I’m tempted to buy the boy all the books he wants. Haggling over investing in the growth of a child’s mind is something I can never understand. In the meanwhile, many hurried phone calls have been made and a blurry sequence of events and a day later, we find ourselves stuffing hot chicken momos in an entertainingly decorated place called Doma’s Inn. It’s already dark when we step out with our stomachs full, and we walk up to a small white building and up the narrow and steep flight of stairs that leads to a wood-and-glass door. It’s only when we hear the doorbell ring that I’m brought to my senses — we’re at Bond’s house, and I remember that I’ve forgotten to prepare the questions I want to ask him. We walk into a small living room full of books and are presented with the man himself. And then the lights go out.

Electricity eludes us for most of our time there, coming and going in flashes that allow me to take in the sight of the man and his surroundings… fragments. I ask him whether he likes automobiles. ‘Well,’ he says, ‘I used to drive a long time ago, when I used to live in Delhi. My employer insisted that we get company cars and that we learn to drive, and so I did. Then I drove through someone’s wall and had to pay for it, and that was the end of that! But the other day, on the BBC, I saw a car that was being readied to go faster than 1000 mph, faster than the speed of sound. Is that true? If the driver were to honk, he’d reach there before the sound could!’ He was referring, of course, to the Bloodhound SSC that aims to shatter the land-speed record which, by the way, happens to be an education project aimed at inspiring future generations to take up careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. An inspiration, just like Bond and his books.

He’s written hundreds of stories and novels, and a lot of them are for children.

When asked what his inspiration is for writing, he says, ‘People. It’s always about meeting nice, loving people… and everybody else, too. If it wasn’t for them, I’d have little to write about. So I write about them and for them.’ If I hadn’t seen him earlier and known what the 81-year-old looks like, I wouldn’t have believed I was speaking with him in the dark. His voice, though deepened with age, contains the clarity of a mind that’s as sharp as ever. The sentences come out of him with thought and deliberation. I keep thinking of that as we leave his home, promising to be back the next morning to take photographs.

The rest of night is spent at a local tourist spot called Lal Tibba, a viewing spot, if I’m not mistaken. I can’t be sure, because there aren’t many people around and it’s dark. A particularly resourceful friend of ours has arranged for everything needed for a cold night atop an open terrace. We’re not exactly meant to be there, but the chaps who run the place are very friendly and accommodating, and we eat, drink and laugh into the night until it’s time to go home. It’s time to drive back to Delhi tomorrow.

The next morning, on our way out of Mussoorie, we pay Bond one last visit. I ask him if he’s willing to step out for a few shots with the car, but he politely declines. Just as well; those stairs leading up to his house left a 32-year-old me winded. And I certainly don’t want to be the reason for a headline that reads, ‘National treasure sprains his ankle due to persistent idiotic motoring journalist’, so I don’t insist at all. Plus his home is a place I don’t want to leave in a hurry. Without the slightest disdain and with a hint of regret, he says, ‘I get troubled by people if I go out at this time. Shortly before you arrived, there was this girl from Mumbai who left behind a couple of poems she wrote to me. It is such a sweet gesture, but at this age, I can hardly respond to every visitor and letter I get.’ Understandable, I say, and offer my services as a communication responder. ‘Come back next time and we’ll see,’ he responds, chuckling away.

He shows us his writing desk, a normal-sized one with piles of books, notepads and papers on it. It’s in a rectangular room which has two windows that frame a valley and part of Mussoorie. ‘Why here?’ I ask him. He says, ‘I always knew I wanted to live in the hills. And I always knew I wanted to write. Delhi’s proximity is good for my work because a lot of publishers are located there. Also, here, people tend to leave you alone — except for tourists! It’s not so bad here, really, but yes… it used to be better. That’s how it goes, I suppose.’

Mentioning his Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan awards elicits no great response other than, ‘Well, it was certainly an honour. But I don’t know how I got those, because you have to be on good terms with the powers that be to be considered for those awards, and I’ve never really concerned myself with such things. I’m happy just getting my cheques from the publishers!’

The living room has photographs of Bond in varying stages of life. It’s clearly been a long life that is just as rich in experience as it is in imagination. Maybe that’s why I’m having difficulty speaking in anything but superlatives and absolutes, and I can’t help but ask him what he thinks is his greatest achievement. The answer isn’t something I’m expecting and the quickness with which it comes is just as surprising. ‘It’s maintaining my independence. It’s the biggest reason for me being who I am.’

Before I can register that answer, he’s showing me a big notepad; it’s his autobiography that he’s working on. He writes with a pen and he writes on paper, not on a computer or a typewriter. Page 155, it says. He says he’s halfway through it. ‘Reading is the greatest help for writing.’ ‘I like looking out at the valley, it’s not a bad view.’ ‘This is my rubber plant. It’s growing quite fast. One day, I’m sure I’ll wake up to find it choking me!’ ‘I’ll always keep writing. Even after writing for more than 65 years, I still enjoy it.’ Time flies by with Bond saying things like these and me trying to soak them in. It’s a happy place to be in, the home of this old man and eternal writer. I don’t want to, but it’s time to go.

Standing at his door, with me saying lingering goodbyes (he probably couldn’t wait to see the back of me), I take a long look at Bond. I simply cannot come to terms with the unfairness of bodies growing old while minds remain young and become richer with experience. Here is a man who should ideally live forever in the hills and keep writing till the world runs out of ink. I want to say a lot of meaningful things to him, but all I manage is what sounds like a threat to see him soon again and an awkward salutation as I head down the steep stairs towards the waiting A3, Ruman and Harshit. The drive to Delhi begins now, though I embark on it in a much better state of mind than expected. After all, who better to see you off from Mussoorie than Ruskin Bond, right?

AUDI A3 35 TDI

The A3, if you didn’t know already, is the World Car of the Year 2014. Yes, it’s quite an achievement.

The A3’s design is flat, wide and compact. It certainly helped in the traffic jams and narrow roads of Mussoorie!

The A3 35 TDI’s 1968cc four-cylinder motor makes a stonking 143 bhp, goes from 0 to 100 kph in 8.6 seconds and hits a top speed of 215 kph. Fun? You said it!

The A3’s 6-speed dual-clutch S tronic gearbox gets different modes tailored for different driving conditions. It even has a manual mode for extracting maximum performance.

The elegant interior has a pop-up screen that displays all vehicle information. Audi MMI system is intuitive and interactive which adds to the convenience.

Ruskin Bond

Born on 19 May 1934, Bond is a legend in our times, a prolific writer whose works are read all over the world.

Bond has played a big role in the growth of children’s literature in India. Many of the stories, essays and novels he’s written are for children.

He is of British descent, but is very much an Indian and has received many national awards, most notably the Padma Shri in 1999 and the Padma Bhushan in 2014.

He wrote his first novel, The Room On The Roof, at the age of 17.

After living in the London and Delhi, Bond moved to Mussoorie in the early ’60s. He’s lived there ever since.

At the time of writing, Bond was working on his autobiography. Lone Fox Dancing: My Autobiography is now available for purchase!

PHOTOS Harshit Gupta