Picture this. You’re in the Czech Republic, in the picturesque countryside not far from Mlada Boleslav, Skoda’s headquarters. It’s a glorious summer day, perhaps a touch too warm (especially for Europe). You’ve just finished downing an excellent lunch, and what remains of the day has been set aside for driving. There’s no dearth of choice, either — on hand are Octavias, Superbs, Kodiaqs and Enyaqs, most of the vRS persuasion. All you have to do is ask for the key and set off. What would you do in this situation? How would you figure out which car to plump for?

For me, the decision was made laughably easy by the presence of another Skoda — a Felicia from 1961, in an eye-catching shade of pastel green. Skoda had lined it up as a kind of showstopping element, among all its contemporary cars — and it certainly halted my show. ‘I want that one’ I instantly said. ‘Are you sure?’ asked the lady with all the keys; she seemed a bit puzzled that I wasn’t hankering after a more modern piece of machinery. ‘As sure as that car is green’ I said. She called one of Skoda’s classic car team members over, made the necessary introductions and left me to it. I realised some delicate negotiations would be required, since it became clear that he was going to drive me around in it, whereas the exact opposite scenario was what I had in mind. Nevertheless, to begin with I placed myself in the passenger seat; the diplomacy could come later.

The Felicia, for the uninitiated, was a drop-top 2+2 seater that Skoda produced between 1959 and 1964. It was a very popular model outside of Skoda’s home market, but the elegant car didn’t exactly fly off the shelves in Czechoslovakia (as it was known then), mainly because it was on the pricier side, and because the country’s brutal winters weren’t exactly kind to convertibles. However, in 1960, Skoda began offering a removable hard top, for better protection from the cold — but that apparently needed about 20 minutes to assemble and dismantle, and needed two people who knew what they were doing.

The Felicia wasn’t Skoda’s first rodeo with open bodywork, either; the firm had been making such cars since its inception, beginning with the L&K Voiturette A. In the 1950s, there was a brief period when convertibles weren’t offered, at which point some employees decided to take matters into their own hands. They came up with a design called the 440 Export, a convertible based on the 2-door Spartak sedan (the Octavia’s predecessor). This led to a series of working prototypes, until Skoda made a production car — the 450 Cabriolet — in 1959; the Felicia replaced it shortly afterwards. It made quite an impact at various motor shows around the world — not many expected a car like that to come out of the Eastern Bloc.

It was a light (930 kg), uncomplicated and robust car, like most Skodas. A central tubular frame was surrounded by a metal body, mounted on rubber bushes. All four wheels had independent suspension; at the rear, torsion bar stabilisers did duty, while coil springs were provided up front. The engine was a front-mounted, longitudinal, 1.1-litre, 4-cylinder petrol making 50 bhp and 7.3 kgm, and it sent power to the rear wheels through a 4-speed manual transmission. It was shared with Octavia, although it spat (coughed?) out another 10 bhp, due to the addition of twin carburettors, a new camshaft and worked-on combustion chambers. What did all this result in? A claimed top whack of 130 kph and a miserly 11 kpl fuel economy figure, enough to keep the four occupants happy on all counts. Skoda made just under 15,000 units of the Felicia (and the later Felicia Super) between 1959 and 1964. The Super had a larger 1221cc, four cylinder engine with two carburettors, and the engine put out 55 bhp and 8.3 kgm; it also had wider tyres, and a slightly higher top speed of 135 kph. The Felicia and Octavia were the last of Skoda’s longitudinal, rear-drive layout models, with the Czech firm readying the 1000 MB, with its engine at the rear.

The chap from Skoda (let’s call him Jan, mainly because I’ve forgotten his name) eased the car out of the parking lot of the restaurant that was serving as our base; between us we had roughly two words each of English and Czech, so all conversations/ negotiations were going to have to be thoroughly improvised. He peeled off onto the main road in the manner of a getaway driver from the car’s era, causing its rear to swing out just a little; some corrective measures with the steering wheel brought it back in line, and we were off at a jolly clip; this was already looking promising. The car’s exhaust note had just the right amount of fruitiness to it — a bit of bass, a bit of braaaap — and soon we had turned off the main road, onto a great stretch of winding country road.

Jan was clearly in his element; his long blond hair was flying about in the wind, and he had the smile of a man who was living his best life. He clearly knew the car inside out, because it responded like it had known him for a long time too, responding smoothly to his every move. I decided that this was the best time to begin preparing to broach the topic of my getting behind the wheel, and indicated to him that we needed to stop for some photographs; he found a suitable backdrop and parked the car against it.

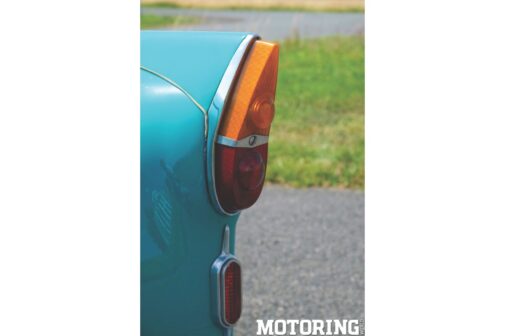

This Felicia was the first facelift, shown at the Geneva motor show in 1961. The grille was made more distinctive, and the tail lights became drop-shaped; this made the rear more striking, combined with the new fins on the flanks. Other changes included a fuel-lid unlocker in the cabin, and the gear lever being moved to the floor, in order to aid quicker shifting. It remained a very pleasing car to look at — simple and without fripperies, combining sportiness with elegance. The cabin was tastefully kitted out, with cream leather seats (extremely comfortable) and cream/black dials; mod cons included storage pockets on the doors and… that’s about it.

I popped the question to Jan, mainly through gesticulation. ‘May I drive it for a bit?’ He pursed his lips for a couple of seconds, clearly taken a bit off-guard. Then he smiled and said ‘Sure, no problem.’ I wasn’t sure why he agreed so quickly — maybe it was the glorious day, or perhaps my charming personality — but I certainly wasn’t hanging about to find out. I quickly occupied the driver’s seat, and took a couple of moments to familiarise myself with the controls; Jan plonked himself in the passenger seat. A gentle twist of the key was all it took for the engine to fire up instantly, and I took extra care to slot the gearbox into 1st; the last thing you want when someone allows you to drive their car is the dreaded grinding of gears. The clutch bit about 3/4th of the way into the release of its pedal, and I managed to set off without jackrabbiting all over the place.

Thankfully the country roads were absolutely clear, so I had the leeway to get the Felicia up to a certain amount of speed. The engine was no slouch, either — it was free revving, and the gearbox was quite smooth too, once I got the hang of timing the shifts. In a straight line, the car was well planted, and the steering wheel didn’t have too much play (as some cars from that era tended to have) so before I knew it, I was cruising at a healthy 80 kph with a broad grin on my mug. When the road began to twist a bit, I took the first few corners slowly in order to figure out how the car behaved (and also to not annoy Jan); a bit of squirming from the relatively thin tyres became evident, and quick cornering required some accurate calculations about where to plant the wheels, but again, once I became used to what the car was telling me, it was all systems go.

There are few things that are more satisfying in the automotive world than driving an old convertible rapidly, in the sort of conditions for which it’s been built, and I can tell you that I extracted every last second out of the time that Jan allowed me to drive the Felicia. Did I regret not grabbing the keys to one of the other cars? Not one bit; I could have bet the Felicia had more character than all of them combined. Skoda may not be the first name to spring to mind when it comes to vintage and classic cars, but the Felicia is right up there among my most fun experiences in motoring.