Of all the ideas my brain has come up with, few have been as questionable as this one. Me, a rapidly-widening motoring journalist, up against a Dakar crusader and one of the best motorcycling talents India has produced. And I thought it was only fair to put us on two diametrically opposed Royal Enfield motorcycles — CS Santosh on the Bullet 350 and my smug backside on the new Himalayan, both setting times at the BigRock Dirt Park MX track. You know, to have a realistic chance of salvaging whatever was left of my dignity at the end of the day. Also, he’d never ridden a Bullet, any Bullet, ever!

For a pair of 40-year-olds, CS Santosh and I couldn’t be more different (a bit too obvious, no?). Other than the fact that when I came up with the idea while riding the new Bullet for the first time, and when Santosh heard of it a few days later, we both laughed. Another connection between us is Ex-Man Ashok George; many years ago, I used to bully him into doing some actual work for this very magazine, and nowadays he works (fingers crossed) as the business head of BigRock. Oh, and finding out that Santosh and I are of the same age may or may not have mortified me; I genuinely thought he was in his late-20s, to which his response was a commonly used unprintable phrase. Time to get nonsedentary, methinks.

Anyway, at the beginning of the day, I found myself sitting across Santosh with a notebook and a pen, frowning with surprise at an unexpectedly broad statement: ‘Geopolitically, India is doing big things and people are looking at us. New bikes are opening up new possibilities. And BigRock as an entity allows people to follow their passion and experience adventure on a motorcycle. But that’s only one element; it gives riders an avenue to discover and express their capabilities. Big Rock also works with people and manufacturers all over the country. It’s a private limited company, a fact that I’m proud of, and part of the Indian movement that enables people to do more and more. Right now, we’re present in two Indian cities, with more locations on the cards, and we plan on expanding into Southeast Asia soon as well.

Even as my pen threatened to burn the paper it was rapidly traversing, I thought, ‘This broadness of thought is the story of every single person who has built their life around the feeling of riding a motorcycle.’ Santosh started out with two races at the MMRT on a TVS Fiero at the age of 17; he finished second in one and crashed out of the other. Not much later, he discovered that riding off-road came more naturally to him, and that it was also more affordable. He could use his bike, a TVS Shaolin, to go to college and tear up a dirt track. Over the next decade, and several national and international victories later, he saw that motorsport in India wasn’t really a viable career choice. So, in 2012, he raced in the Raid de Himalaya for the first time to say goodbye to racing — and won it in record time. Some things are just meant to be.

And then came the injuries. In 2013, he suffered third-degree burns that took a year to recover from. In 2021, he had a fast crash at the Dakar, something he’s still recovering from. After the last one, everything changed. And that’s when he realised why he clicked with Red Bull and Royal Enfield as brands: ‘It’s because of who they are as people. It’s about the storytelling aspect of life and the brands. This is to do with questions about life — and the Dakar gives him elements of the answers. The most important aspects are people and feelings. Even when we ride motorcycles, it’s because of and for the feelings. The Dakar is a reflection of life itself. Preparing for the Dakar is preparing for life. And speed comes second to the art of living. The Dakar, like mankind’s and its own history of migration, is ingrained in all of us.’ That migratory aspect applied after his big accident as well. ‘I realised that I was not constrained by my culture or who we are. There was no definite answer to life — the answer was simply doing it for the art and the experience.’ When asked about that level of commitment, he replied, ‘It’s not a conscious effort. Everyone has energy that needs expression, and this is who I am. It’s not about a definite period of training, it’s become my lifestyle. It’s constant.’ I got the distinct feeling that things tend to get philosophical rather quickly with Santosh.

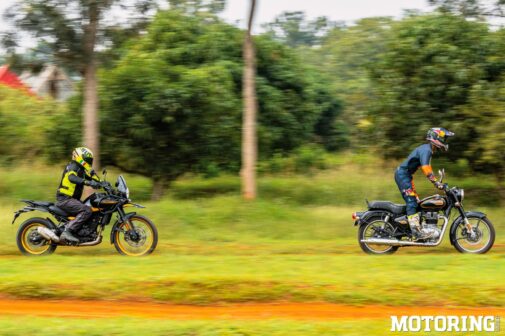

I suppose thinking of a distant land with a certain purpose in mind can have that effect on someone. And It’s difficult for someone like me to understand such a single-minded attitude to life. Again, both of us like being on two wheels, but our mindsets are as far apart as Mercury and Pluto. And the velcro around the waist of my riding jacket groaned whenever I bent forward; if Santosh is an athlete, I have secured my position as a fathlete. And he was certainly measured in his responses, as elaborate as they were, perhaps a bit too much for my liking. Then again, he made up for that by throwing the Bullet into never-seen before shapes, so it was all forgotten.

Watching Santosh size up the Bullet was quite the incongruous sight. His off-road gear was in stark spatial, intentional, temporal and philosophical contrast against the hand-painted golden pinstripes on the tank. And he was riding the Bullet for the first time, though I could’ve sworn he’d done it many times before. I asked him how many laps of the place he’d done, and he laughed in a way that clearly implied he’d never ever considered such a thing — clearly, there would never be enough. And so the Bullet sang along at high-rpm around the track, as I watched it appear and disappear from my vantage point atop the parked Himalayan.

Santosh’s riding, even on the road tyres, was fluid and smooth. His throttle hand was clearly in harmony with every inch and undulation of the track, and that made the exhaust sound almost musical. At times, the Bullet would appear on top of a rise, glide down the slope, and hit the rev limiter all the way to the next sweeper. Its riding position was the furthest from an off-roader, but Santosh made it work like he wanted. It went up a berm, the inside footpeg tapping the earth like a demented woodpecker, and then out of the corner, its two wheels always delightfully out of line. And yet, it was always effortless.

Santosh’s fastest time on the Bullet: 3 minutes and 8 seconds. Never mind the milliseconds — even with all the time in the world, it was never going to get anywhere close to that. Given that it was my first time on an MX track in years, I was more panicked than excited. The greatest fear of my tarmac-fashioned life is a front-end slide, and a 21-inch front wheel’s inherently muffled way of conversing has never put my mind at ease.

Nonetheless, the Himalayan took care of all my fears until I was laughing out at second-gear slides (in a straight line, of course). It was way more fun than I was expecting, always planted and forgiving. Of course, I had to keep its weight in mind, but the bike had all the basic abilities required to learn how to go faster and faster around a track such as this. I pulled off some small jumps, went up and down those steep slopes, and generally indulged in my own stubborn way of riding off-road with my backside firmly plonked on the seat as much as possible. Santosh did ask me to ‘stay in the barbell-lift position’ all the time, but my knee’s complaints were too loud to ignore.

Nonetheless, I know I went faster at the end than the recorded time: 3 minutes 23 seconds. Later, Santosh posted a lap of 2 minutes 41 seconds on the Himalayan, which gives me a lot of targeted scope for improvement in the future. And I know I’m going back way more often, too. BigRock itself is one of the most beautiful motorcycling places I’ve ever seen — and I’ve seen my fair share, mind you. The MX track, all 1.8 km of it, packs in so much learning into a shape that constantly twists and turns around itself. Every time I exited it, I immediately wanted to go back in — and that’s quite an effect on someone who doesn’t like off-roading that much. And for those who want to get close to Santosh’s benchmark time, a fresh batch of new Himalayans was unloaded at BigRock the day we were there. That should start an itch or two, I think.

For Santosh, 2024 brings four international rallies, a warmup to the Dakar in 2025 — what else? It has been a tough road for him, in more ways than one, though this year promises new beginnings. Alongside his own comeback, BigRock Motorsports has launched its own team in the Indian Supercross Racing League, and this endeavour goes back to Santosh’s first students: ‘Many years ago, I taught two blue-collar gentlemen how to go off-roading. I was surprised that I quite enjoyed it. So now, I’d like to groom the next generation of homegrown talent. See, I am selfish and I want to live forever. If I can live through other people, then I choose to do so!’ Quite right. After all, we can’t be part of this world while trying our best to be as far away from it as possible. Or, as Santosh proves, we can if we try.