As a 13-year-old, my favourite place to ride was to the old paper mart. Once every month, I’d arrive outside a ragged old shop, squawk the horn at the store owner and ask for my copy of Business Standard Motoring. In exchange for ₹3, he’d hand me my copy, which I would then neatly stow away into the apron-mounted boot of my father’s LML Vespa NV. A pop of the front wheel later, I’d race home to pore over the contents of that magazine at an obsessive rate.

By then, I was already four years into reading BSM, having begun in my bicycling years. There was no way I could afford to buy a magazine off the shelf, of course. My father, meanwhile, kept a close eye on my reading material, often offering to ‘make some room’ in the home we lived in, a characteristic feature of which were magazines stacked up against several walls. He hated the idea of letting me near motorised two-wheeled contraptions (he still does, in fact) and saw that my stack of magazines wasn’t exactly helping his resentment. Fortunately, I’d had the foresight to self-appoint myself as one of the delivery boys of his small but popular restaurant on Mumbai’s outskirts. This meant, in the interest of profitability, I soon graduated from pedal power to becoming a two-stroke-powered human slingshot.

Inheriting his Prussian blue NV brought tremendous clarity to my life. I’d only flirted with gearless scooters a bit until then (I lowsided a cousin’s TVS Scooty the very day he brought it home) and I remember struggling to comprehend I finally had access to my own set of two wheels and an engine. My grades plummeted almost instantly and, soon, I dropped out of the school football team as well. We were a properly rubbish team with a reputation for spectacular losses anyway. And while others my age were ‘falling in love’ and experimenting with beer and cigarettes, I had my hands full trying to tame ‘MAY 5103’ over 200-metre long wheelies. The only money I had (tips, from delivering food orders) was quickly spent on filling the NV’s tank with the right proportion of petrol and 2T oil poured from sachets. What was left was used to ration second-hand copies of Motoring and, at times, a few other magazines.

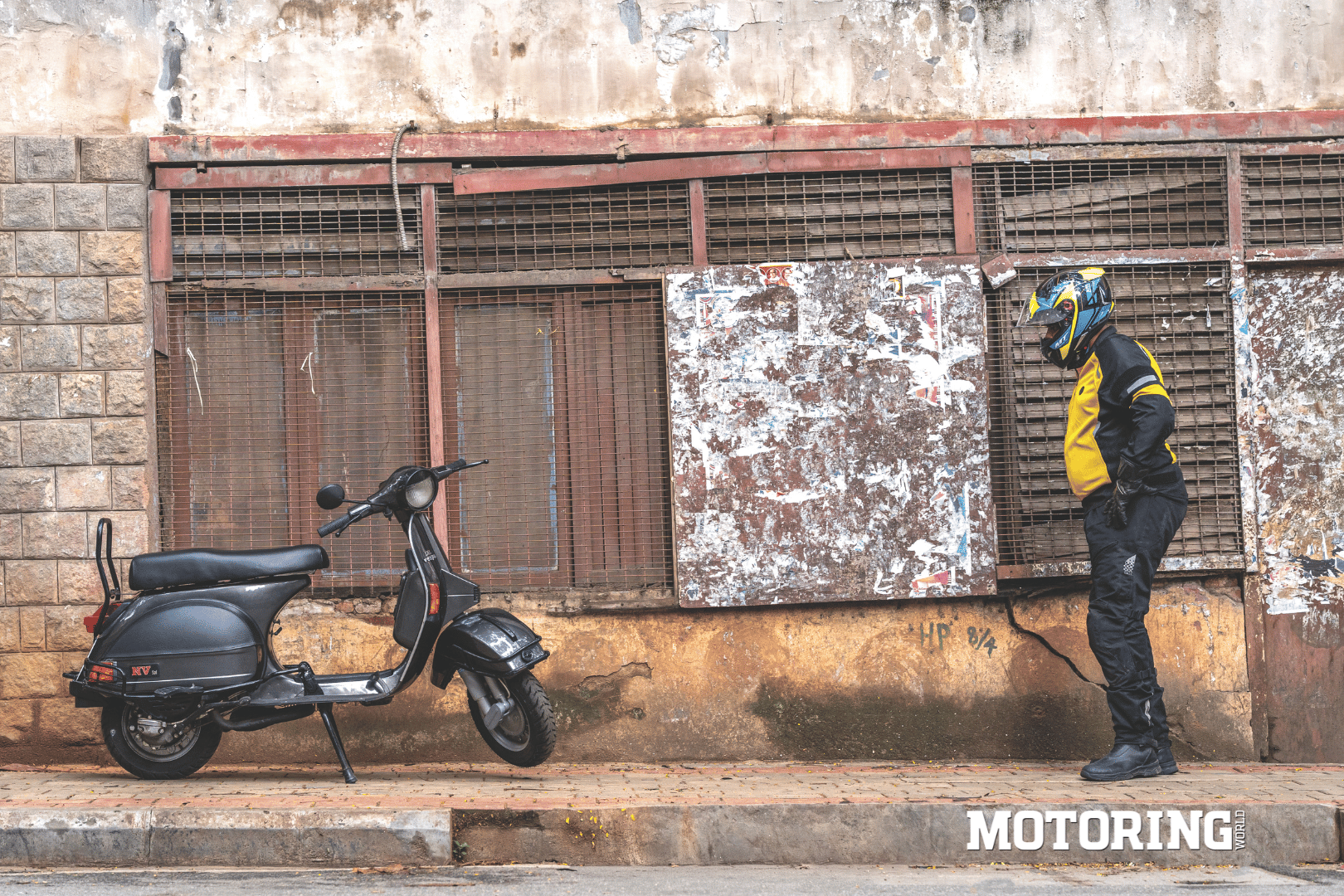

I knew I was going to end up here. It was only a matter of time. It’s incredible how muscle memory works, no? In the 20 years that have passed since I last rode an LML NV, it would seem I’ve made it a point to grow larger. Life, since I joined Motoring in 2010, has been as much an endless rush of fast bikes as it has been of fast food and, I’ll admit, I do come in the way of some smaller machines these days. That I could find my way around the NV so elegantly came as a pleasant surprise with, perhaps, an undertone of shock. Karan Lokhande, a friend whose generosity and enthusiasm for the stories we come up with knows no bounds, helped source this NV in Bengaluru. And he knew exactly why this mattered so much.

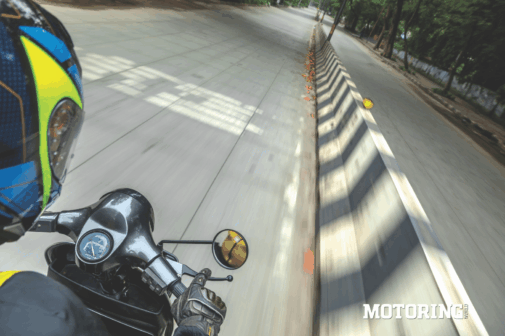

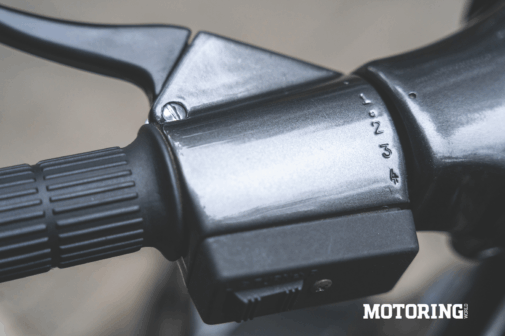

My gloved hand reached for the key slot and then the underseat fuel tap with practised precision, and my left (now race-boot clad) foot landed perfectly on the kick-starter. It sounded familiar if not identical and, in an entirely flawless manner, I’d plonked it off the centre stand, snuck the twist-shifter into first, and rolled forward slowly. Deja vu? Can’t say. I’ve never ridden an NV slowly before! Back in the day, it was either standstill or flat-out, interspersed with wheelies and going stupidly sideways on the rear brake.

My reference point those days was Shumi, the MotoFocus motormouth (by his own admission) who shaped my early motorcycling years with his wisecracks and hard-nosed opinions. Later, we would become friends and ride together on work trips, something I still find a matter of great disbelief. Around the same time, although ironically at an Autocar India event, I met Bijoy, with wife Rekha and kids in tow; Miura, his little daughter, was perched atop his shoulders. Over the next few months, I began pestering him on Orkut and, eventually, Facebook. At the time, Motoring was defined by its people — so I wrote embarrassing messages to all of them, hoping someone would notice. Kartik did, over an unscripted chat in the dead of the night and, the very next day, I was handed an offer letter with a typo; it mentioned a salary I wouldn’t withdraw for the next three years. It didn’t matter. I was at Motoring now, being incomprehensibly given a column to write and the ‘Ferruccio’ nameplate to live up to.

I didn’t know where I’d fit in — if at all — but I’ve never wanted anything more than I’ve wanted to be there. Or here, I should say. It’s not the same thing, actually. Never mind.

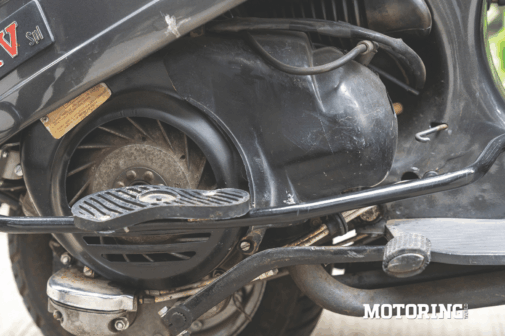

The NV was a properly fast scooter. For somebody who is entirely unenthusiastic about motorcycles and cars, my father always sang praises of its 149.5cc two-stroke engine. He believed it was far superior to the Bajaj Chetak, which he disliked for its small (8-inch) wheels; the NV had 10-inchers. He never actually rode fast, though. Speed skips a generation, I suppose, so I just had to take it upon myself. I learnt riding (or operating the scooter, to be more accurate) purely through observation; I’d made up my mind about it for years before I was allowed to ride.

One summer holiday, our chef, a lean, tall Nepali gent named Jivan was appointed my riding coach. As we set out for my first tutorial, I simply asked him to play pillion and took off, flawlessly. This was years of visual learning finally being put to the test. He’d been given a month to bring me up to a decent level and here I was, expertly going through the gears, diving into corners and braking with precision. So, for the next 30 days, I’d simply park him under a tree alongside a long strip of desolate tarmac, where he sat listening to his Walkman and chewing tobacco, while I’d ride in accordance with the agenda I’d set for the day. It was just 30 days of burning petrol mixed with 2T oil. I’ve never had that kind of uninterrupted riding time ever since.

An 8-bhp two-stroke scooter in the hands of a helmetless teenager may not have been a great idea in hindsight, but it did me huge favours. This was a time when my friends had already started riding proper motorcycles — RX 100s, Victors, Calibers, CBZs and Pulsars, to name a few — and I outpaced every single one of them on the NV. It’s quite embarrassing to say so myself, but I was seriously fast. It’s a scary memory. Over time, the sound of a scooter hitting its redline in each gear with precision became a matter of terror for the community we lived in. I didn’t think I was up to anything extraordinary at the time, though. To me, it was the only way to ride anything. When I’d stop to chat with my few remaining friends, I’d verbally plagiarise something I’d read in Powerband, Shumi’s column in the magazine.

I went through clutch cables at an alarming rate and, at some point, figured I didn’t really need one. I later learnt tapping the rear brake pedal would create an effect using which I could power-wheelie in first gear. The handlebar would get all crossed up when hoisted and the side-mounted engine meant it always threatened to land a little sideways. I still wheelie that way, even on motorcycles. Most of all, though, the NV felt invincible. It was hardy, a bit brutal and, astride it, I simply never felt vulnerable. I didn’t even today, despite now being wired to expect the best of componentry. There’s a confidence to the NV’s stride, enabled by its ample wheelbase, tall stance and inherent agility that’s evident to this day. I can’t say I wasn’t tempted to return to some of my antics.

We had to move cities, eventually, and the NV had to stay behind. I was asked to leave it at the doorstep of its next owner and I did so understandably grudgingly. Oh, I was a mess that afternoon and, I think, I’ve been quite poor with goodbyes ever since. That wasn’t going to be the last time I’d been asked to walk away from something I dearly loved, though. In any case, I’d have done nothing differently even if I had known.

Motorcycles happened eventually and, with them, came evolution. There was a part I realised I hadn’t yet figured out — ‘You’ve made it to Motoring, now what?’ I thus began to dream differently. Those dreams, over the last 15 years, manifested in the form of stories, machines and beautiful places. They also earned me friends, above all else, who are the only constants in this continuum, as I place a 26-year-old dream onto its centre stand and walk away from it, one last time.

What also remains is an irrational love for the NV. I’m afraid of it, too, because it confronts me with qualities I thought I no longer possessed. It makes me feel like a teenager again. It makes me dream. And I really could do with chasing a new one.

We’d like to thank Digvijay and Dilip G for lending us their scooter for this story, and to Karan Lokhande of Motomatic Restorations for working his magic, as always.