Photographs Sherman Hale Nazareth, Samuel Ribeiro & Tank Up

If there’s one thing that’s become increasingly common on any of my two-wheeled adventures, it’s the element of coincidence. There’s no way either Sam or I could have remotely imagined two months ago that we’d be cruising amongst mountain clouds on a couple of behemoths that are designed to decimate distances in utmost comfort. Of course, these distances took on a more vertical dimension than the horizontal ones these machines are normally accustomed to. While the fates manifested, our Himalayan adventure slowly began to take shape.

As with coincidences and the innate nature of Goa to have sporadic spells of intermittent electricity, I decided to ditch gadgets and pick up a book in my collection that I hadn’t read yet. As I got past the first chapter, neurons that had never connected before did. The book, of course, was the 1895 classic, The Time Machine, by H. G. Wells.

While the time traveller may have used a contraption so flamboyant it’d have been right at home as a carnival float, I’d like to think of the majestic BMW R 1300 GS and the enormous F 900 GSA as our versions of that time machine. They all are immensely complicated machines in their own rights. Only instead of going into the future like the time traveller did, we went back in time as we got higher up into the mountains.

Our little adventure began in Delhi where we picked up the BMWs. The plan was to ride to Volume 7 of Tank Up, which was being held in Kaza, Spiti Valley. Long-time friend, Vir Nakai (co-founder of Tank Up), and I had discussed showcasing a film I’d made riding two classic Urals with sidecars up in the Altai Mountains in Southern Siberia, Russia. Needless to say, I decided to take him up on the offer.

Now, this wasn’t a ‘curated’ ride like journalists are used to these days. A plethora of questions and a well of anxiety filled my mind before our trip could even begin. Nonetheless, eyes wide shut into the adventure we dove. It was just a regular Wednesday, but the amount of traffic on the Delhi-Chandigarh highway meant it wasn’t an easy cruise. We were riding a bit north of Nahan that day since I wanted to skip Chandigarh and city traffic. Boy, did I underestimate the scorching Haryana weather.

And then finally, some respite emerged as we approached the Himachal Pradesh border. Hills started to appear on the horizon. The initial ascent was slow and tedious and the unrelenting heat was strong on our heels. The roads gradually got twistier and narrower, and the scenery lovelier and lonelier as we ventured further up. The final approach to our homestay was steep and no more than a paved walking path. But as the saying goes, ‘The harder the path, the better the reward.’

We were finally in the foothills of the Himalayas. The haze from the lowlands was still visible below us, but at least the weather was better. The cool mountain winds blew down as the evening settled in. Despite being weathered from the hot day of riding, I was eagerly looking forward to the next day. It was when our actual adventure would truly begin.

The start the next morning was a pleasant one. We took the inner road to Solan and then turned onto the main Chandigarh-Shimla highway. The aroma of pine trees wafted through our helmets, a stark contrast to our previous day of riding through the plains. Impeccable tarmac along almost the entire stretch meant the endless stream of corners got us into quite an idyllic rhythm.

Back on the highway, the traffic had made a reappearance. Luckily, despite its curvy nature, the highway is wide enough in most parts to allow driver idiocy and utter lane indiscipline to be calmly ignored. But it was crossing Shimla that I wasn’t looking forward to. Shimla is beautifully located and the people are polite, but the ever-increasing city traffic and narrow hilly roads are always a pain to navigate. But the further away you get from Shimla, the better it gets.

Eerie web-like structures were plastered all along the mountain sides on the way to Narkanda, the misty atmosphere adding to the spookiness of it all. As we got closer, though, these turned out to be apple orchards with protective nets draped over them. The evening in Narkanda was a chilly one, our first taste of the weather to come.

We’d be riding to Nako the next day so it was an early start. We had a good 250 km of mountain roads ahead of us, but the day began with the descent to Kumarsain and then crossing the perpetually crowded town of Rampur Bushahr, a remnant of the exploitation of Himalayan resources by the British Raj. Post that it was a wide-open highway running east beside the Sutlej River for the most part.

When we made our rest stop a little further down the road, we like it was frozen in time. I knew our journey back through the dimension of time had begun.

While we were completely and utterly spent, a warm meal of chowmein and a glass of fresh apple juice rejuvenated us, while views of snow-capped peaks lay what felt like a stone’s throw away. We were now at an altitude of 3625 metres and could definitely feel the drop in oxygen. Nevertheless, this was our first night of acclimatisation and it was a rough one.

Thanks to Kunzum pass still being shut due to snowfall at this time of the year, our final stop along this route would be Kaza. The next didn’t initially notice the magnificent and sacred Kinnaur Kailash peak peeking between the mountain tops. We were now getting into the upper Himalayas and one of the western edges of the erstwhile Kingdom of Tibet. The landscape slowly transformed around us into a harsher, drier landscape as the presence of snow-capped mountains became increasingly prevalent and greenery less so.

A little after Pooh, we crossed our final bridge over the Sutlej River and from this point forward it was the Spiti River we’d be riding alongside. Well, not for too long. The road soon ascended via Khabo Loops and I was left completely dumbstruck. What was a complete off-road section when I did it last in 2022 had now transformed into a glorious impeccably paved road that made the towering desert mountains seem a lot less inhospitable than they actually are.

When we got to Nako, we had a 2-km ride off the highway to our homestay. And this is where the time traveller slowly came into play. As we made our way through the narrow village roads lined with stone houses and an abundance of Buddhist prayer flags, Nako felt morning, we loaded up the luggage, a routine we had now fully gotten used to at this point. Thankfully, the winds weren’t as brutal as they were the previous day and the morning sun warmed our bones. After a slight climb to the nearby village of Malling, the next section was the descent back down into Spiti Valley. The road remained spectacular — a far cry from what I recalled. It stayed this way all the way to the Sumdo checkpoint.

The winter snow had not been kind to the road surface. Here, the road was narrow and void of guard rails. By now, foliage was almost non-existent and a ragged rocky wall lay around us. The next 50 km of gravel sections, broken roads and cliffside trails were nerve-racking. It was either a 100 per cent focus on riding or your loved ones would be getting an unfortunate call some time later.

We finally made it to Kaza by noon. The revelry at Tank Up had already begun, so Sam and I checked into our hotel and rested a bit before partaking in it. When we did actually get there, it was pleasant to run into old friends that we hadn’t seen in a while. The last time I’d met Karanbir, part owner of Hotel Deyzor and ex-automotive journalist, was back in 2022 on my last trip to Spiti.

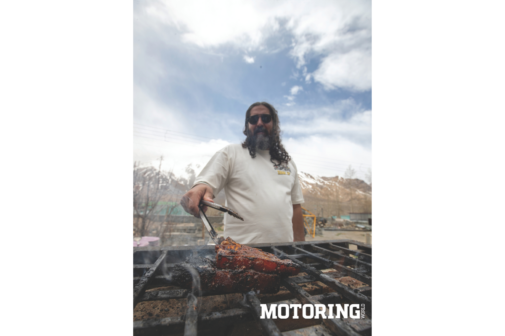

Hotel Deyzor is the most curious of places; from the thoughtful phrases from various cultures written on the walls, to the abundance of books that line its shelves, it certainly is a place to behold. But for now, it was time to warm ourselves with some of Vir’s fabled pork chops straight from the grill. Chats with old friends and introductions to new ones by the fireside filled the rest of the evening. And just like that, time had warped back to the present, far from the true essence of Spiti Valley.

This was early May and summer hadn’t really set into Kaza yet. The days saw the mercury climb to about 5 degrees, while the nights saw it drop to -2. I decided we’d ride up to Tashigong the next morning to soak in a bit of the altitude. As we crossed through Key village, our dimensional course was rectified and we were again transported back in time. The traditional Tibetan architecture that surrounded us was a stark reminder of that. Not to mention the 1000-year-old Key Gompa which stood stoically above all of it.

Riding these massive BMWs up past 4300 metres certainly was a daunting task but also equally fun. It wasn’t just the scarcity of oxygen at these altitudes, it was the sheer drops, tight hairpins and slushy ruts created by the melting snow that made it more so. Here’s where the weight of the bikes was making its presence felt. We rode as far up as we could before we mentally and physically exhausted ourselves. I’d ridden up to Tashigong before, but never in early May. This was the first time there was so much snow around. When we stopped before turning back, I just sat to soak in where we were. The snow-capped peaks weren’t in the distance any longer, we were among them.

For the 15 minutes or so that we just sat there, it felt like eons of thought had passed through my head. I could certainly understand why for thousands of years, nomads and monks alike wandered these mountains in search of nirvana. At these lonely altitudes, the terrain had been perfectly preserved, and it felt like a window into the past. Since we all come from the same primordial soup of the Big Bang, it’s like looking into a little long-lost slice of yourself up there. After all, aren’t we just a complex assembly of carbon atoms and processes that make up this very universe we live in?

The next morning, Sam and I were scheduled to start our journey back down. Instead, I was awoken with excruciating pain radiating from my abdomen; a personal and internal big bang, if you will. It was a pain I was all too familiar with, yet another kidney-stone episode. There was no chance we’d be able to ride back that day, and as the day progressed, the pain got worse. It was an enormous 8-mm stone that had already been troubling me for a few months prior; none of the painkillers or alpha blockers seemed to work. I knew I’d have to rough this one out, but what I didn’t know was for how long.

A plethora of questions filled my mind as I’d completely lost all concepts of time. Would I be able to even ride back? Would I need surgery? The closest hospital was in Chandigarh — a whole three days away. The outcome seemed bleak so I decided to just let the day go and see what happens. The constant dull pain stayed with me through the day and the night.

Then at 5 am, it vanished. A miracle, I thought; I still didn’t know if the stone was out or not, so instead of wasting any time, I woke Sam up, got us packed and on the bikes and by 9 am we were off. It was all surreal at this point; I didn’t know whether the pain would make a reappearance, so I just rode as fast as one can in the mountains.

Once past the Sumdo checkpost, we were back on buttery smooth tarmac and the bike was back in Dynamic mode. We were holding speeds I never dreamt I’d ever do in the mountains — and that night we celebrated the fact that I had made it past the kidney-stone ordeal. The next day, we rode back to Narkanda where it was still chilly. The ride was uneventful for the most part. We did, however, run into some magnificent Himalayan vultures feasting on horse carrion lying beside the road. On the ground they were a dawdling awkward bunch, though.

As we packed our luggage one last time (or so I thought), I still couldn’t believe the trip we emerged from and were wrapping up. The BMWs were back in their element, and after the harsh conditions we’d ridden them through I was shocked at just how comfortably the R 1300 GS absolutely decimated the highway distances. After the mountains, I’d forgotten what these bikes were really made for.

We’d gone from sea level in Goa, where the deafening din of insects and frogs most of the year are a clear indicator of the favourable conditions for life to the parched mountains of Spiti, where the absence of ambient white noise indicates the exact opposite. Yet, despite the hardships, the Tibetan folk seem like a much happier people.

Could there be a connection between H. G. Wells’s divergent post-human species of the Elois and Morlocks and the future of modern-day humans? The time traveller does, after all, travel 800,000 years into a dystopian post-apocalyptic future. By that logic, just maybe, the Tibetans got it right so many centuries ago. Maybe this teleportation into the past we just encountered on our ride is an actual glimpse of the future. Maybe it’s something we all need — a sense of fulfilment that goes beyond the self and its immediate needs.

P.S. I’m extremely glad to report that on returning to Goa and getting the necessary scans done, that troublesome kidney stone is nowhere to be found. I may just have unknowingly contributed to Spiti’s count, and I hope it confuses the heck out of some geologist someday.