Have you ever tried telling the same story twice? Oh, well, you do it all the time, no? Of course, your story gets more exciting with every new narration and, perhaps, a bit more dramatic, too. That thing that absolutely did not happen? Go on, make stuff up — who doesn’t love a little gasp from the audience, right? Even if the refinement of your later attempts lack the candour and innocence of your first, a good story is almost always worth repeating. Especially if you can somehow wait 30 years between doing so. Just like Bajaj has.

No, the ‘other’ bike here isn’t the result of someone’s imagination having been let loose at the aftermarket parts store — it’s a Bajaj SX Enduro. Launched in India exactly 30 years ago, the SX Enduro was no success story, although it perhaps best represented what was brewing inside the Bajaj HQ in the mid-’90s. I’ve lucked out with a really stellar source for this story, so we’ll go deeper into that in just a moment. There’s another motorcycle here, too, one you instantly recognise as the KTM 390 Enduro R, manufactured, of course, by Bajaj. Its popularity isn’t documented yet but I can safely say it has already outdone the SX Enduro’s, seeing as no one ever bought the SX.

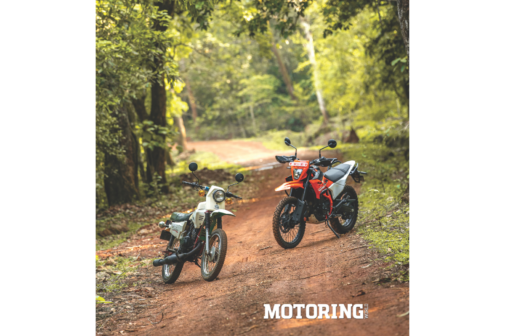

Bringing them together, therefore, wasn’t a matter of choice. It was a reunion forged in floppy plastic, the signature of bikes in this class. Jayanth Mavalli, a thorough two-stroke motorcycle nut and a dear friend, happened to have two SX Enduros (okay, so someone did buy it!) in his vast garage, and it took very little provocation for him to have one tidied up in time for our story. Now, SX Enduros were offered in the brightest of colours — red, green and purple being the ones I remember of the lot — and while the one you see here isn’t stock, the fact that it’s survived three decades in the thick of a dense Karnataka forest justifies allowing it some creative licence.

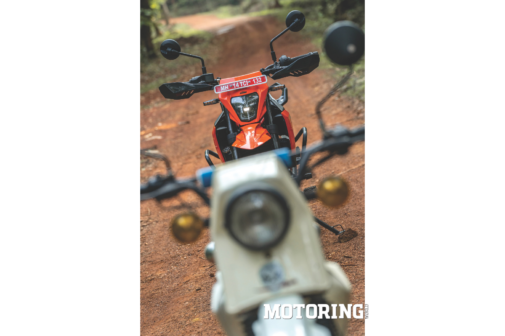

It was in said dense forest (remember the Ducati SuperSport story from two issues ago?) that we chose to bring these distant siblings together. I mean, what better than an endless labyrinth of forest trails sheltered by towering trees to try out two off-road bikes in the middle of a hot summer, right? Understandably, we were off into this exciting trail in an instant. The pleasantries could wait. The SX led the way, leaving a beautiful trail of blue smoke in its wake, while the KTM followed patiently, barely engaged given its relatively tremendous power reserves.

If you were expecting a dogfight, I’ll have to disappoint you. That wasn’t the point of this reunion at all. See, the SX Enduro was a quick motorcycle, powered by its two-stroke KB100-sourced 99.7cc, roughly-11-bhp engine, designed to beat performance standards of its own era, something it didn’t necessarily do on all counts. The 390 Enduro R is the current benchmark — miles ahead of anything in its class. Sure, they’re evenly matched on intent, but, in execution terms, they couldn’t be more apart. One is the product of unrestrained youth, the other, of finesse.

Fortunately, I had the privilege of digging deeper into the SX’s story thanks to Adil Jal Darukhanawala, the father of Indian automotive journalism and, to so many of us, an ever-encouraging and helpful spirit. For a decade before the SX was launched, Adil, who was then the editor-in-chief of Car & Bike International also handled the Bajaj racing team, a dominant outfit that won nearly everything in sight in the late ‘80s, across Sholavaram, Barrackpore and Yelahanka, among others. It was on his insistence that Bajaj had managed to import a pair of Kawasaki dirt bikes (Bajaj had a tech JV with them back then) and, eventually, Adil found himself huddled with the Bajaj leadership to come up with a motorcycle that would have an edge over the class. It wasn’t an easy league of motorcycles to beat — the Yamaha RX 100 for its outright performance, the IND Suzuki AX 100 for its versatility, the Hero Honda CD 100 for its 4-stroke economy and Bajaj’s own KB 100 for its dynamics. A few months would pass before Adil would unexpectedly be thrust the keys to a new-ish motorcycle Bajaj had chosen to call the SX Enduro.

While the SX didn’t make much of a mark on Adil — it lacked outright power, the brakes were so-so and it looked dated even back then, being inspired by late-’60s design standards — it spoke volumes of Bajaj’s spirit of enterprise. In Adil’s own words, the SX Enduro was a ‘baptism by fire for Rajiv and Sanjiv Bajaj — the new, young blood of the family.’ Evidently, Rahul Bajaj had allowed them ‘economical mistakes’ and with Joseph Abraham already lining up a potent list of technological advancements for Bajaj (digital ignition and the four stroke Chetak, to name a few), the SX Enduro was a boutique project or ‘Rajiv’s first avant garde move’ as Adil describes it.

His first mistake, too, then? Not quite, given that the SX was developed for the price of peanuts — and in isolation from Kawasaki. The KB’s long wheelbase was retained and so was the headstock angle, its fork tubes were dropped to create longer travel and the suspension components came from Bajaj’s faithful old vendors (Gabriel, Endurance…). Only the dual purpose tyres were all-new purpose built hoops by MRF. It was, indeed, far from a pocket pincher, although it turned out to be a sort of low-cost MBA crash course for Bajaj which, up until then, hadn’t exercised its marketing powers on the motorcycling front. The SX’s (lack of a) success story saw Bajaj deploy its marketing chops towards its next onslaught of four-stroke motorcycles, headlined by the Caliber, the Eliminator and the Pulsar — all phenomenal hits. Lesson learnt, then.

In a somewhat far-fetched way, then, it can be said that the 390 Enduro R owes its existence to the SX Enduro. The learnings of the SX Enduro (from a marketing, if not engineering perspective) helped Bajaj bolster the Pulsar to become the sensational motorcycle it became and, had it not been for Bajaj’s relentless pursuit of refining the Pulsar, it may not have acquired the prowess to be able to take on the high-stakes assignment of manufacturing KTMs in India. In turn, KTM may or may not have survived the aggressive post 2010s without its Indian arm and that, as a result, might have culled its journey short far before it came up with the Enduro. Far-fetched — told you so — but it’s a solid theory, no? Let’s debate that over a cold one but, for now, I have motorcycles to ride!

The SX is as uncomplicated as bikes get. The ergonomics are genuinely superb — the stubby seat, the tall-ish handlebar and the centre-set pegs feel natural — and once I got past the flooding-prone carb (on this bike, that is), it was a riot. That KB100 engine with its disc valve intake and its factory-fitted expansion chamber — yes, it was the first of its kind to offer it (the TVS Supra offered one as an add-on in later years) — makes for punchy performance, even if it lacks outright brute force. I may have looked comical tearing through the forest on it, my exceptionally large proportions not helping the SX’s case, but I had lots and lots of fun. I expected no less of it, based on the premise of it being a light, peppy two-stroke, but the SX’s true strength lies in its agility. I’ve rarely known motorcycles to be more responsive and yet as intuitive and, I promise you, it would have been remembered a lot more passionately had Bajaj raced it and evolved the idea of it for longer than it chose to.

While Manaal rode the SX for the shots — and also hilariously struggled with it, being relatively unfamiliar with two-strokes — I hogged the 390 Enduro, a motorcycle I’ve taken a strong liking to, to say the least. Switching to it from the SX, the Enduro is every bit a reminder of why we’ve to be thankful for the evolution of motorcycles. It’s roomy, it’s well finished and it feels super hardy — the kind of bike you’d want to ride across, say, the moon. And that’s before you even start talking power and torque. Then, it’s smashing. With its 45.3 bhp being laid down through chunky off-road rubber, the Enduro lets you get very creative with the throttle, especially on the kind of smooth, flowing trail we were on. It’s a naturally comfortable motorcycle, with its fantastic suspension at either end, ample travel and clearance, and a proven chassis giving it so much confidence, you can’t help but take liberties with it. If you trust your reflexes, you can even try riding it with its electronic rider assists switched off and, I assure you, it’ll get you laughing out loud inside your helmet.

Frankly, had we not run out of time, we’d have carved a happy little routine out of this. Sliding around mindlessly, pulling wheelies on a whim, attempting all kinds of juvenile antics — that’s what makes ‘enduro’ riding such a likeable prospect unlike its far more life-threatening motocross counterpart. And while the 390 Enduro understandably offers greater headroom to learn, the SX stays firmly in character with its low ceiling that’s densely packed with thrills. If motorcycles are, indeed, an education, the KTM is the equivalent of finishing school, while the SX teaches you the things you learnt in the school backyard during breaks. It’s impossible to overstate the importance of either.

In any case, we wouldn’t dare objectively compare the two — oh, how pointless that would be! What’s to take away here is the significance of thought, of intent and of doing all you can, with all you’ve got. It’s a poignant coincidence that both these motorcycles happened to their makers while on the brink of tremendous financial turmoil. While the SX, although almost by accident, laid down an early stepping stone for Bajaj to tide over its crisis, it may also have unknowingly aided Bajaj to help KTM overcome its own. History really does have a sense of humour, eh?

We’d like to thank Jayanth Mavalli for loaning us his SX Enduro for the shoot and Adil Jal Darukhanawala (@adiljal on Instagram) for his invaluable inputs.