THUNDERCLAP

It is no surprise that Motoring’s first modded machine was a café racer. After all, nothing showcases everyday grit and purpose more than this species of caffeinated two-wheeler. In 2003, only Pablo was around when our founding editor, Bijoy Kumar Y, rolled an innocent Royal Enfield Thunderbird into a workshop to be fashioned into what you see here. For at least two of us back then, it became a template of what was possible in life. The Thunderclap was equal parts beautiful and awkward, like life itself, with the former more than making up for the latter. Oh, how freeing it would’ve been to ride a motorcycle like that in a time that was actually closer to the original café racers than the handful of factory-made slicksters we’ve gotten since then.

In a time when Orange County Choppers and Biker Build-Off were the hottest shows in town (both overwhelmingly stupid in a typically American manner), building a café racer took some original thinking that was tethered to reality. Yes, there were no exotic parts on the Thunderclap off the Hitchcocks catalogue. Yes, it was built on a budget that was probably smaller than today’s average Starbucks bill. But it gave our readers something to stare at for hours, days and months on end, something that’d stay in their minds for years to come. And that something was hope. Mating a café racer ’bar to the standard mid-mounted ’pegs? Erm, not much hope in that, we’ll admit.

SB1100

Never let facts get in the way of a good story — in hindsight, that seems to have been the brief for this build. It helped that no one really knew what the facts were or how the story would turn out. Bijoy launched this project with the only intention he’s ever had — of seeing things through. Whatever memories remain, though, are a bit fuzzy. What is certain, though, is that at some point a Premier Padmini found itself at the mercy of an idea — to be turned into a convertible. Or as is only apt to say in the Italian way, a barchetta.

A rally-prepped engine was lugged across airports, the body was cut straight through the middle to lower its stance, the bonnet was perforated in the shape of a NACA duct for a bell-mouth filter to pop out of, and the shell was subjected to a number of reinforcements that’d make any army envious. It had a top… no, a cover that protected the seats. And the driver’s line of sight was always met by the A-pillar frame, so the only way to drive it was by leaning out over the door. But it sounded and felt glorious, like a festival on four wheels, wherever it went. And to think, it all began on a piece of paper in an office. Isn’t that just amazing?

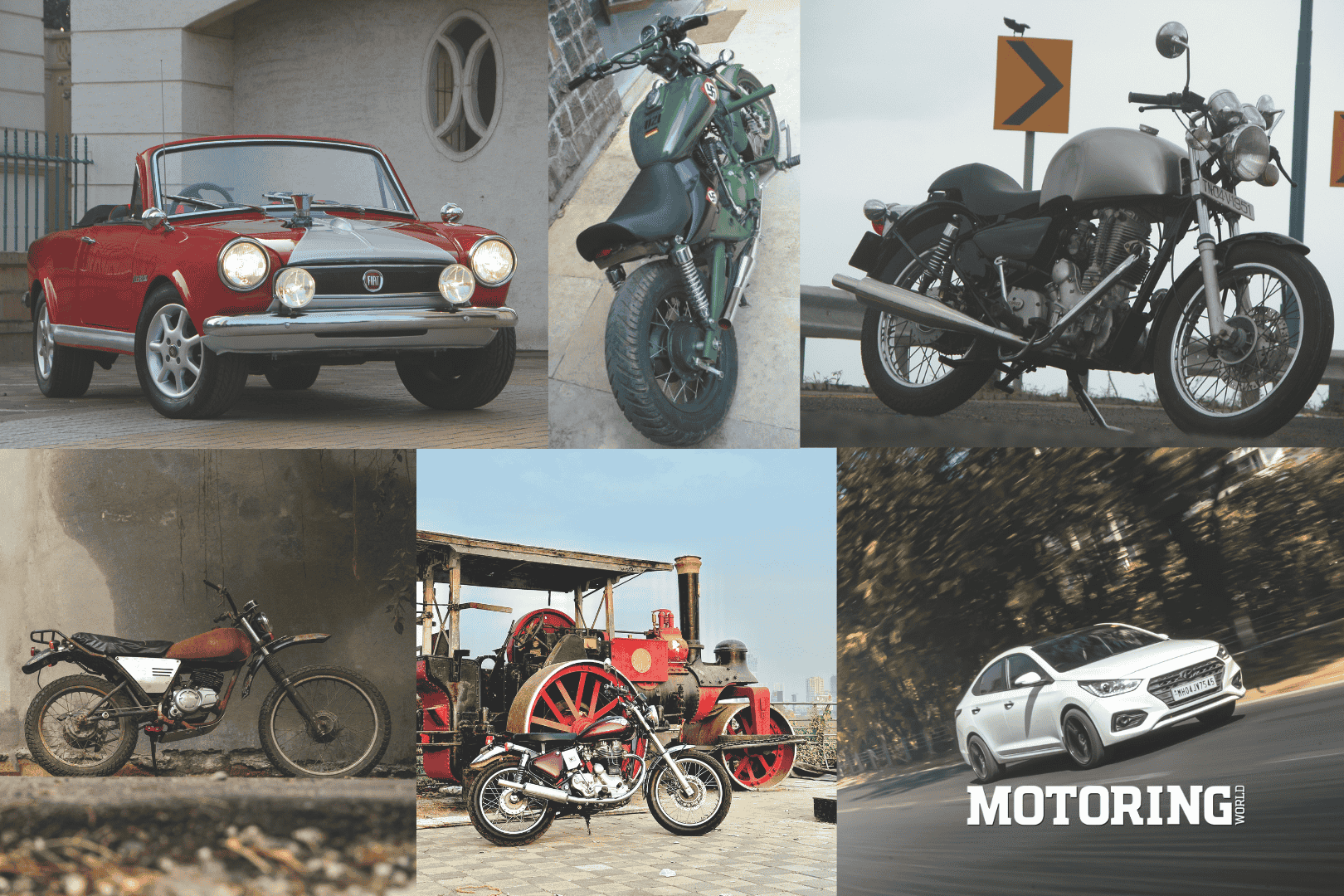

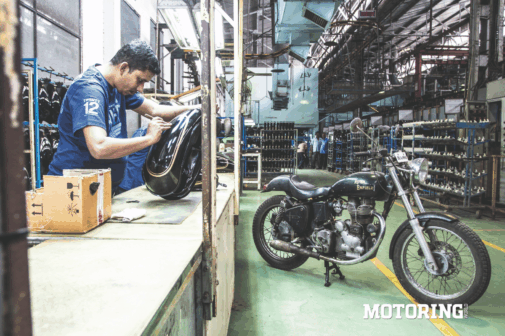

THUNDERSTRIKE

Okay, you’re getting the idea — we’ve always liked café racers. This machine fantastically filled the cover of our eighth anniversary issue in 2007, commissioned as it was for the occasion (yes, by Bijoy). Built by Akshai Varde of Vardenchi Customs, the Thunderstrike was an ode to the Motoring spirit. Obviously, it couldn’t be boring, and coincidentally it was also Vardenchi’s first non-cruiser/non chopper build. Yes, we’re infectious like that.

Long, low and silver with dashes of yellow and red, the Thunderstrike was a sight to behold. In fact, one of us was waiting at a bus stop on the way to college when Varde himself rode this bike past. Obviously, that chap will never get over café racers in his lifetime, and he even turned his own cast-iron Bullet 350 into one… or at least tried to, with inevitably disastrous results. But sparks like these don’t fizzle out that easily, do they?

SLEDHAMMER

Oh, do forgive us for preening about that absolutely brilliant name. Inspired by old British metal that once thundered across the Baja desert (which we’ve never been to…), this was a build that we somehow put together with Royal Enfield’s custom division in 2023. Somehow, because it wasn’t easy. And it was a good thing that we had friends like YC Design and Bombay Custom Works who knew what they were doing. We were only along for the ride.

Based on an Interceptor, the Sledhammer ended up as far as it could from the benign twin given the rules — no engine mods, no alterations to the chassis; it had to be a plug-and-play affair. Sometimes, restrictions do make for fun challenges. Form over function, comfort over bravado, common sense over logic — the Sledhammer tested all of these notions, and then some. It was stupidly loud, as all straight-piped customs are wont to be, and so well put together, the handlebar rotated forward the first time it was jumped. The most important thing to this day, though, is what it gave us — memories of time spent as it should be.

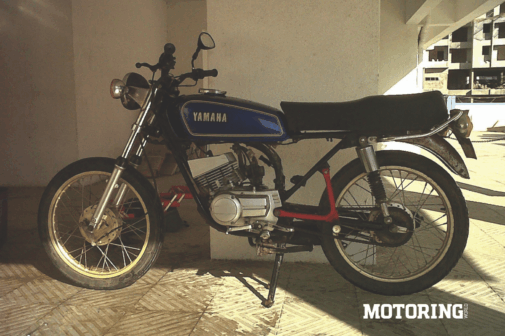

VERNA

It’s true when people say cars are an extension of one’s personality. They’re woven into our stories, from the thrill of a first drive to countless family vacations. They witness our adventures, milestones, and even our messier moments. Over time, we trust them with our safety, our loved ones, and in some ways, our emotions, too. After all, who hasn’t spoken their heart out behind the wheel, or shed a tear when no one was watching? That trust often turns into a deep, unshakable attachment.

For me, my Hyundai Verna — lovingly called Panda — is exactly that. Which is why keeping it stock was never an option. I wanted it to reflect me, and since sneakers are my other obsession, it only felt right to get Panda its own pair of kicks, too. To be fair, it isn’t like the Koreans had done a bad job with the Verna’s aesthetics, but I always felt it needed more character. That thought snowballed into a spiralling slope of modifications, and Panda became my canvas.

I began small. The roof got wrapped in black vinyl, the chrome bits disappeared, and the alloys went up a size, from the stock 16s to a sharper-looking 17 inch set. Inside, the beige trim gave way to black, and I swapped out the stock audio for a custom Alpine setup, complete with a 12-inch subwoofer to keep the audiophile in me satisfied.

The alloys, though, are a story in themselves. I had my eyes on one specific design that I knew would suit Panda perfectly, but tracking them down was an ordeal. After exhausting every dealer in Mumbai, I finally found them through a Thailand-based manufacturer that makes alloys for Indian cars. Seven months later, they arrived, and since then I’ve been obsessed. Keeping them spotless is another full-time job — but honestly, I don’t mind.

Now, I know that, unlike some of the wilder builds featured here, Panda’s story isn’t radical yet. But that’s the beauty of it — it’s still evolving. With more time (and maybe a little more money), I’m certain the next Mod Special will have a whole new chapter to tell.

SUMMER KAMPF

Ever tried to design a motorcycle on MS Paint and gave up mid-way? I did and didn’t, in that order. And that’s how I destroyed my first-ever motorcycle. My used 2002 Kawasaki Eliminator was on a good run until a regrettable brainwave struck a 19-year-old me. Up until then, it had miraculously survived my attempts to ride it off-road and, with a theoretical assumption based on its long wheelbase and rear footpegs, I had tried hard (unsuccessfully) to get my knee down on it. Bored but raring to unleash my unfortunate creativity over one particularly slow summer, I decided it had to evolve into a loud, irreverent chopper.

To be truthful, I had started out with a drag racer in mind, but with nobody except a very enthusiastic civil works fabricator at hand, we decided to stick to a chop job. Using an early version of Google Translate, I figured I’d call it the ‘Kampf Maschinengewehr’ and then proceeded, with no intervention, to paint it military green, with decals bearing the Nazi swastika (I apologise) in prominence. It didn’t end there. Decals were cheap, so I got a few more made; a German flag and the logo of Israeli arms manufacturer Uzi are ones I remember. This geopolitical mess then inherited a free-flow exhaust (I think they were called rocket silencers). We chopped a bit of the rear sub-frame off, got a fab seat made and, now emboldened by the promise of possibilities, decided to make our own kicked-out footpegs using a pair of L-brackets and a welding torch. That list bit wasn’t the poorest of ideas I’d had, as you can tell.

Man, that motorcycle was loud. It would shoot flames on downhill runs and I think I was quite proud of it at the time. A month or so later, Bijoy sent a typically encouraging message on Facebook asking me to file a report on it for Motoring’s (then BSM) Reader’s Rides section — an absolute dream come true — and while I can’t remember a word of what I wrote, I do remember sending in a dozen or so photographs, pained expressions and all.

At some point, a rat (you are free to assume its race) chewed through pretty much all of its wiring, and while I did send it over to a friend’s workshop to be rescued, he never really got around to doing it. I suspect this had more to do with the questionable livery than the unavailability of parts. The last time I saw it — a decade ago, easy — it had sunk halfway into the ground, sort of easing into its own grave.

Lesson learnt? To some extent, yes. A year later, I bought a Yamaha RX-G with my first salary at Motoring and, armed with a vague idea of how to build a street-tracker, set about sourcing parts for it. The handlebar came from a Yamaha FZ, the conical air filter (utter crap) came from Bangkok, and I gave it the world’s most beautiful cheap paint job ever. At this point, I ran out of money to give it rear-set footpegs, new tyres and a disc brake, but it didn’t matter. Although I didn’t see it this way at the time, it was inherently rubbish to ride anyway. Sold it a couple of years later and didn’t regret it one bit. Needless to say, I’ve been on better behaviour since. If you ignore that Bajaj Super I road tripped and scrapped, that is.

CAFE COMMUTER

Of all the builds listed here, this is probably the most cost-effective and unimaginative one. After all, we were just three teenagers with a couple of thousand bucks and a lot of spare time. This bike was gathering dust for almost a decade, so it couldn’t possibly have gotten any worse. The first day was spent cleaning the bike so that it could be pushed to the garage. And the mechanic’s estimate left us with around Rs.1500 — enough for a paintjob, new lights, exhaust and tyres? Nope. But we didn’t have any choice.

And if you are from Mumbai, you’d know the obvious place to source cheap motorcycle parts — Kurla. The ‘SE Project’ exhaust cost us Rs.450, a set of indicators and tail-light for Rs.300, clip-ons for another Rs.300 and three cans of spray paint for Rs.450. We’d spent all the money our friend had and we still needed more.

With no source to get more cash, we started working on the bike. The luggage rack, side panels, and the leg and saree guards were removed. It was repainted in patchy matte black with random stickers. Our friend’s mother popped by once to see what torture we were subjecting her late husband’s bike to, and perhaps out of pity, lent us more money. I guess it was the same feeling that also led the mechanic to weld the exhaust for us for free. He even threw in some exhaust heat wrap to hide the ugly welds.

Three weeks later, we had a loud, lightweight café racer running on second-hand tyres. But it didn’t take long for a cop to catch my friend, call his mother, and the bike to be parked back in its place to gather dust again.

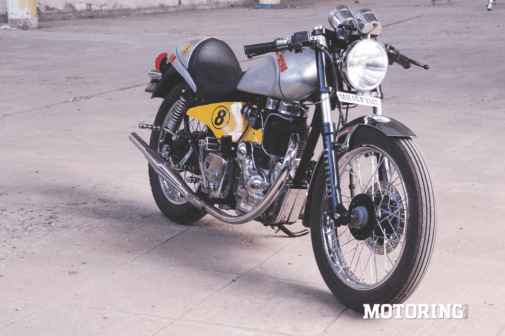

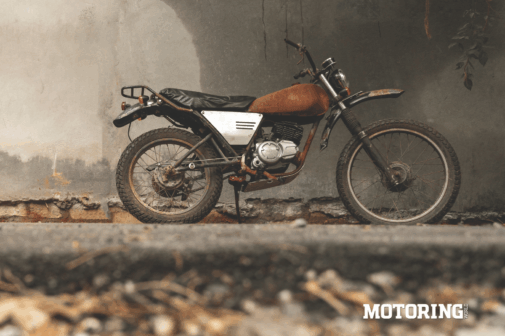

YAMAHA RX—

Yeah, I don’t know if this bike will ever get finished. I’ve been at it since 2008. It used to be a ratty Yamaha RX 135 with a 4-speed gearbox and a banged-up expansion chamber. The first thing I did was to paint it all black, beating all Indian motorcycle manufacturers except Bajaj to the act. It had a big red ‘BSM’ sticker on the top of the tank. But it was still stock, and it wasn’t long before I got bored of it. And so, off it went to be turned into a café racer. Yes, I know, and I can’t help it.

There’s a reason you only see the blue frame here; I still feel bad about letting that form of the RX be ripped apart. It was a proper little missile, even if it didn’t like changing gears or using its rear brake too much because of the inches of flex caused by the extravagant linkages necessitated by its extremely rear-set ’pegs. It had R15 tyres, the stickiest ones I could find in 2009, mounted on two Bajaj 17-inch rims (wanna guess which ones?). And it had lots of anodised bits and bobs from the R15’s aftermarket catalogue, along with proper clip-ons from the newer Yamaha, too. The fun I had riding that thing, well, that cannot be recounted in a respectable magazine. But then, some years ago, it had to turn into a street tracker, and that’s where it stands now. With an RD 350 piston and porting to leave Space X rockets feeling inadequate. Can’t wait.

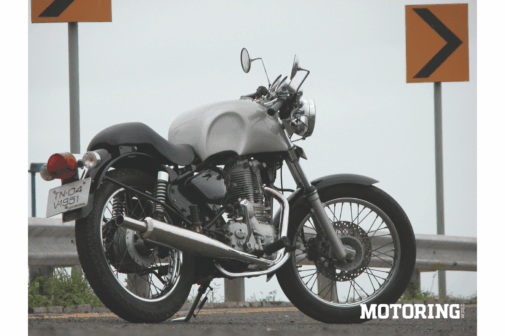

BULLET 350

I’ve never been much for naming my motorcycles. I’d much rather just get on with the business of connecting with them. And this Bullet you see is the first machine I felt that connection on, before I even rode it, and that has been the story of my life ever since. This motorcycle was never stock, thanks to my father; he bought it before I was born and when it had a sidecar. Then he detached the offending carriage and added indicators not meant to be on this motorcycle. All manner of metal guards surrounded the thing. Then, when he sold his RD 350 as scrap, he kept its fork and bolted it onto the Bullet, claiming it improved braking. Of course, it did no such thing.

Many years later, I pestered him into finally restoring it because I was embarrassed to ride it anywhere. Then, after he passed away in 2010, I was free to do whatever I wanted with it, but couldn’t bring myself to… well, except put on a loud pipe, a low ’bar and rearsets on it. Many more years later, I decided that enough was enough, and that the Bullet had to become what it was always meant to be — the most beautiful tribute to the man who loved it more than most things in life. And that led to the violet work of art you see here. It’s been three years since it assumed its current form and I still can’t stop staring at it. Neither can anyone else. It still blows its bloody head gaskets every year, though.

There have been many modded machines in Motoring’s 26-year history, though feel free to leave aside what that says about us as a bunch — it’s what it means. The only real tragedy in life is always a lack of imagination.