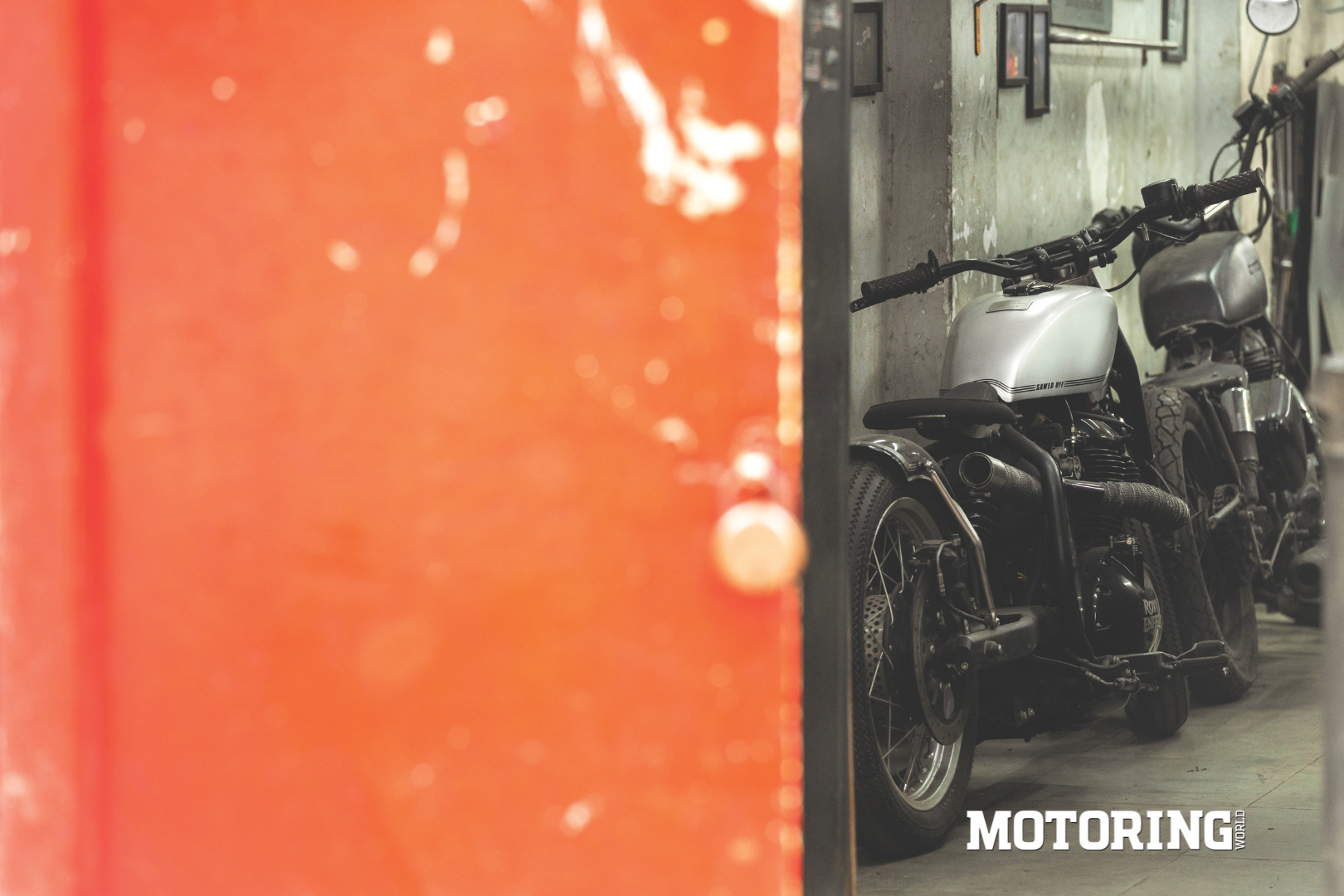

‘Don’t do it.’ — that’s the honest advice Shail Sheth has for aspiring custom-motorcycle builders. Which is a bit strange, considering he himself has been running an outfit called Bombay Custom Works for 13 years and counting. Another quasi aphorism from Shail that easily contradicts the first — ‘I’ve always said yes first, no matter what the job, and then figured out how to do it.’ Which was a surprise the first time I heard it; the end results of whatever rolls out of his workshop made it seem that he always knew what he was doing. He is also the only health conscious hypochondriac I know… but that has nothing to do with motorcycles, so we shall let that be.

Being terminally addicted to custom motorcycles, it came as no great surprise when I ended up orbiting around the gravitational attraction that BCW exerts. And my life has been all the richer for it. The fact that Shail is a friend has no bearing on my objectivity, I assure you (in fact, my friends would rather that I didn’t write about them at all, since my observations have been from close quarters, in varying degrees of consciousness or the lack of it. You’ll see what I mean shortly).

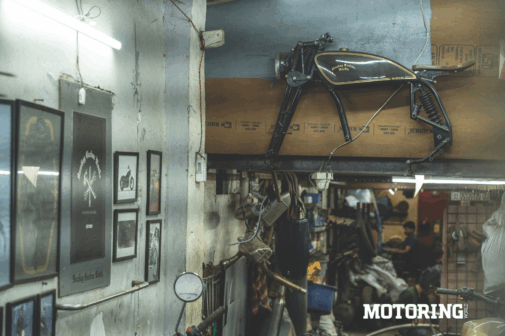

BCW’s creative process usually begins with Shail holding his head in his hands, with a facial expression usually found in the most busy room of a maternity home. And its origin story’s comic quality is matched only by its founder’s knack for theatrics. After getting a bachelor’s degree in automotive design from Coventry University, UK, Shail landed in the US to become part of the automotive design industry there; to this day, I cannot imagine him merging with Detroit’s Motor City history. He’d stick out like a soft thumb, I’m sure. Not long after, he found himself in Delhi… designing mixer-grinders, door handles, fans, coolers, beer caddies, and so on — what happened to motorcycles?!

Well, he was never a motorcycle guy, to begin with, his attention was firmly on cars. Then, he got his first motorcycle, after being encouraged by a friend, a Yamaha FZ-16. And then he happened to see some custom motorcycles at the Auto Expo, and asked himself that very important question — ‘I can also do this, right?’ As it turns out, he could indeed do it. But not before getting bored out of his mind in a formal-clothes business environment because his father asked him to come back to Bombay and join the family business. Some people just have to do things the hard way, you see?

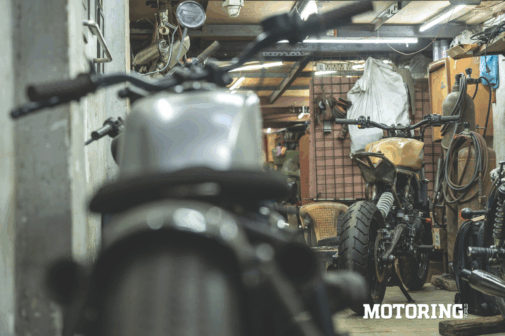

And that was when he stripped down his first project motorcycle. It was a second-gen Bajaj Pulsar 150, and he tore it apart just for the sake of seeing what he could do with it. Then, someone saw the finished motorcycle on social media and asked him to display it at India Bike Week. Back then, almost all custom motorcycles in India were based on Royal Enfields, so a custom Pulsar was a bit of a novelty. That set off a trickle of orders, a bike here and a couple of bikes there, and before long it became a gushing stream of customised metal.

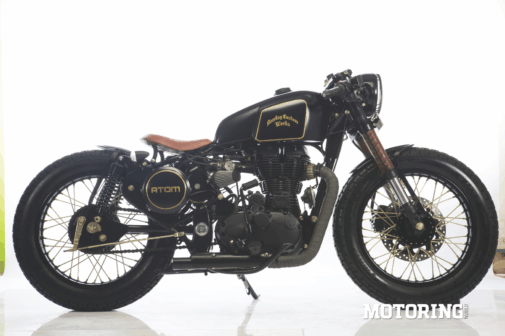

When I asked him about BCW’s hallmarks, or its vibe, so to speak, his reply was immediate: ‘Old-school, and a pure approach to the material, be it metal, leather or wood. There has to be an honest treatment of the design and manufacturing process. Inspiration comes from everywhere, but I try to be as original as possible. And only by being honest to the material at hand can I be that. There was no specific reason to design a motorcycle; I wanted to create something that would add value to a motorcycle. I am a designer first, and for me a motorcycle is a medium of expression. But I just like to design things for the sake of it.’ The 3D printer on his desk and the motorcycle luggage he’s made are proof of all that, I suppose.

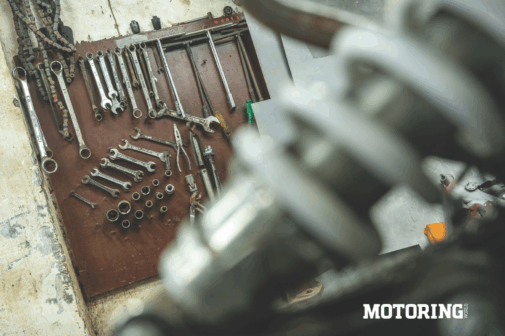

And what has he learnt in the past 12 years of running BCW? ‘Even if I graduated as a designer, I knew nothing of engineering and manufacturing, so in the past 12 years those aspects have been my biggest learnings. And making the biggest impact using simplicity. If you have a white sheet of paper, that itself is one of the most powerful designs ever. The simpler, the better, the bigger the impact.’ ‘Also, nothing is ever a one-person job, it’s always a team effort. Even I am only a part of the process, I can’t do everything on my own. If my fabricator tells me he’s happy with the finish of a job, I know that’s the best job possible.’ ‘And there’s always a point where you stop. You have to learn to say that this is enough, I don’t have to do any more. There’s no need to overcomplicate things. That understanding of when to stop is something I’ve learnt over the years. That’s also how I think the best bikes are made.’ All talk of stopping doesn’t apply when you invite him to speak, though.

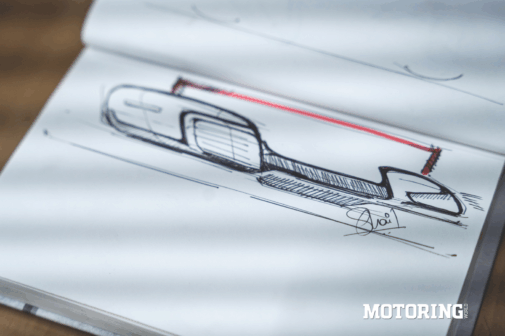

But what makes him stop in the motorcycle-building process? ‘It’s like spraying perfume; too much or too little won’t work, it has to be just right. It’s the fine line between beating metal and repairing it. It’s an emotional thing, not everyone might get it, and that’s fine, too. And I rely on the people around me to tell me that something is done as well.’ ‘Another important thing is to plan and execute. If you start without a plan, you’ll go on forever. Planning helps finish a project faster and better. Planning helps achieve a flow in any process.’ ‘And you have to ride bikes to build better bikes.’ That is attested to by that fact that BCW has worked with nine different two-wheeler brands making concepts, prototypes, custom builds, consulting for design, and manufacturing of accessories, among other things. That’s in addition to making motorcycles for a famous cricketer, a less famous actor and a most famous alcohol company (go figure). I can’t say I’ve heard of any third-party outfit achieving that level of depth in the OEM space.

Time to get philosophical — what is design? ‘Well, one is the practical side of it, and the other is the aesthetic and emotional side. One makes life easy, the other makes you feel good. With respect to a motorcycle, it has to look right, and then I can move on to design something to make it work. For me, function follows form. Take cleaning a bike for example; I want to make motorcycles which people will love cleaning. Integrating that interaction with a motorcycle is part of the thought process that goes into making it; decisions about materials and finishes are always taken based on these things.’ Shail says he’s influenced by German designer Dieter Rams’s ten principles of good design. Even if he has to look them up on Google if I ask him to list them on the spot. You should, too.

Over the past few years, BCW’s method and the person in question may have come across as chaotic to me, but there is a deep rooted fundamental attitude and knowledge that form the bedrock of the place. More importantly, Shail exemplifies the importance of never stopping to learn and to always be curious about everything. As for his unencouraging statement about building custom bikes, don’t listen to it — go ahead and build as many as you want. And if you need any help, feel free to ask Shail; he never turns anyone down. As every BCW motorcycle proves, learning is the real design, after all.