Nobody writes prayers anymore. While religion has grown to influence the political landscape and sociological fabric of the world, isn’t it odd that prayer has entirely evaded refinement? How, for instance, has it escaped the attention of religious bodies around the world to induct the Ducati 916 into the holiest of verses? It isn’t just a Ducati, after all. It’s the Ducati. The most beautiful of them all.

It’s a motorcycle writer’s nightmare, the 916, because it makes you really question your calibration. There are simply so many cliches, so much conditioning around it that it becomes challenging to separate reality from propaganda. Yet, as it stood before me with its sorrowful eyes, I became unable to overcome the urge to feel its face, a feature that has haunted me for practically all of my life. I carefully ran a gloved thumb over one of its headlights and it made me want to cry. Motorcycles don’t always do that to me. Okay, years ago, a Benelli TNT 25 did, too, but that’s because it blew its ECU in the middle of exactly nowhere in Rajasthan. And so did the new Panigale V4 S.

Before you write me off as a complete emotional wreck, allow me to clarify, it was purely down to how uncomfortably locked-in I had been on the Panigale thanks to its brutally aggressive riding position. I sought relief from short bursts of acceleration, but those were as effective as slapping a Band-Aid strip onto a landmine injury. Thirty minutes astride it had made me question all of my life’s decisions and as an overcast Bengaluru morning threatened to add to my overwhelming discomfort, I could do little else but to pray it would all be over very soon.

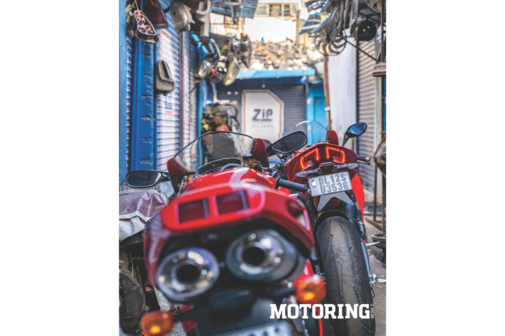

There is a God, clearly, because it showed up in the form of the 1998 Ducati 916 Biposto you see here. I blurted out an unscripted ‘wow!’ as I approached Chezian Natarajan, motorcycle designer and the 916’s owner — how’s that for a combination, eh? Not sure he could hear me over the angry din of my V4 S and the dry clutch soundtrack of his own motorcycle, I signalled him to paddle to an oddly buzzing tea shop (it was 6 am!) across the road. For a moment, there was a deafening silence as we killed our engines and over-cautiously kicked-down our side stands. It wasn’t an everyday affair for anyone around, I was certain of it. You don’t simply wake up one morning and find two of the world’s most incredible motorcycles parked in the most ramshackled part of your city, do you?

We were in Shivaji Nagar, a precinct of Bengaluru notorious for its harrowingly cramped bylanes, its sensory overload of an abattoir and, of course, the maze that its questionably-sourced automotive spares market is. It’s no place to ride Ducati’s most powerful motorcycle yet, let alone its most iconic one. Nonetheless, here we were, hoping we’d get by without stirring up a racket. That, the motorcycles were capable of doing all by themselves anyway. A championship-winning L-twin with a comically loud clutch and a MotoGP-derived V4 are hardly bikes you can rely on for discretion. Whose stupid idea was this anyway? Oh, wait..

It’s not always a bad thing, showing up at the wrong place. A young Massimo Tamburini did so a bit inelegantly, specifically at La Quercia, a corner named after a poorly stationed Oak tree, at the Misano racetrack in Rimini, Italy. A mid-race crash astride his Honda CB750 Four left him with three broken ribs and a resolve to build frames that were worthy enough of the brilliant engines Japanese motorcycles were supplied with. A skilled motorcycle tuner, Tamburini owned an air-conditioning and plumbing company named Bimota, an acronym derived from the last names of his friends Valerio Bianchi and Giuseppe Morri, aside from his own. His crash, however, inadvertently gave birth to Bimota’s entry into motorcycle manufacturing, eventually earning him recognition from the Castiglioni brothers, owners of Cagiva, who entrusted him with designing the 1986 Ducati Paso. His aptitude for motorcycle design saw him land the role of designing Ducati’s next flagship, the 916. The rest, of course, is history.

The 916, launched in 1994, wasn’t explicitly born out of a want for beauty, though. It was meant to be a fast, powerful motorcycle, one with agility and tractable power — something the Japanese still hadn’t figured out properly yet, with the exception of the Suzuki GSX-R750 from exactly a decade ago. The starting point for the 916 was, in fact, its upgraded 8-valve engine designed by Massimo Bordi, who introduced the ‘Desmoquattro’ (4-valve) engine to Ducati, first in the 851 and later in the 888 that replaced it. What the 916 lacked in power, it compensated for with its even spread of torque, all of which was available to me as we elbowed our way through impossibly congested alleys. I don’t know how many of you came looking for an objective analysis of the 916, but I’ll tell you anyway — it’s a motorcycle with telepathic levels of responsiveness. It’s tiny enough to blend in with 250s although, as a result of that, its ergonomics are a bit, erm, challenging.

If the 916 was ‘a bit racy’ for its time, the V4 S is an unapologetic track hound. It’s a motorcycle designed by racers, derived from the pinnacle of two-wheeled motorsport and is made, I think, purely for the purpose of racing. I can’t comprehend why you would rationally pick a V4 S for Sunday joyrides other than to brag about it — while clutching your lower back in deep agony, of course. What next? A Sukhoi Su-27 for a private jet? I’ll pass. The V4 S is quite brazenly a thorough, committed race bike built for no greater purpose than to assert Ducati’s dominance in the motorsport world. That should explain its winglets, its 70 million rider assists and, of course, the small matter of the 213 bhp its 1103cc V4 produces. That kind of power can make any sort of motorcycle feel manic, let alone one with a sub-200-kg kerb weight. No, there’s nothing endearingly welcoming about it — it feels every bit as potent as its spec sheet forewarns you.

Before you get to any of that, though, you have to acclimatise to its 850-mm seat height, among the tallest in its class. It’s not a superbike you can flat-foot with ease, especially if you’re vertically deficient and that, along with the extreme downward reach to its handlebars makes it seriously demanding. I get that it’s a motorcycle designed for people not built like Harley-Davidsons, and some track reviews (Manaal rode one at Buriram, Thailand recently) favour it immensely for its intuitive responses, but on the road, I’d rather ride a Diavel — and I hate the Diavel! Kaizad, the only member of Motoring World who understands how a gym works, rode the V4 S on the drop-off run in peak Bengaluru traffic and, let me just say, there have been wars in recent years that have lasted for less than the power nap he took afterwards.

That’s not to say it isn’t impactful. While I don’t think I’m skilled enough to critique it too objectively, having ridden lots of motorcycles of its ilk, I can tell you it’s really special. Making sense of its 90° V4 on urban roads is a tall order, but it’s plainly evident how monumentally superior it is to every other flagship Ducati that has preceded it. The rider assists menu is immense (but also, fortunately, intuitive to explore and configure) and a clear indicator of how electronics-focused Ducati has evolved to become. That’s not to say it lacks the hardware — I mean, its top-notch Pirelli Diablo Supercorsa SP tyres and Brembo Hypure brakes surely make it crash-proof enough already!

The 916 boasts no such frills, as you’d expect from a motorcycle of its time. At low speeds, it’s impossible to look past its agricultural DNA; it feels crude and somewhat unfinished, even if you use ’90s superbikes as a reference point — until you find a chance to wring open its throttle, that is. The beautiful delivery of torque from its 916cc liquid-cooled 90° ‘L-twin’ makes for very relevant performance even today and despite its 100-bhp deficit over the V4 S, it feels like a motorcycle you could take to a racetrack and set a few hot laps on with ease. Okay, so the brakes are rubbish and its tyres are comically narrow, but that trellis frame feels brilliant, especially if you can top it with Carl Fogarty-levels of nuance.

It’d be a bit overzealous of me to claim any real-world benefit from its gorgeous single-sided swingarm layout, though. While Ducati marketed it as a feature to benefit quick tyre changes between races and as a weight-saving measure, I don’t think it was as purpose-driven as that. Ducati, in the past, wasn’t the track-fixated powerhouse it is today. It did things irreverently, often ignoring functionality in favour of design. Indeed, if you were a service technician at a Ducati dealership in the ’90s, you were prone to be driven to clinical insanity. And yet, you wouldn’t hear anyone groan about it because of how hopelessly beautiful Ducatis of the era were. I suppose that’s strongly why, when Tamburini designed half a swingarm for the 916, nobody chose to do anything about it. Interestingly, the new V4 S features a conventional swingarm for the sake of improved lateral stiffness and because Monica Bellucci must have begged for it. Okay, I obviously made that last bit up, but I can’t see why else Ducati would relegate that important a chapter of its design legacy to the history books.

‘Racers can really take the fun out of motorcycles, eh?’ quipped Chezian, when we pulled up for a coffee and breakfast after our shoot. It’s ironic but true. A racer’s vocabulary excludes character and comfort — it’s not how they’re wired at all. Racing is firmly transactional and speed is the only expected outcome. It doesn’t matter if the motorcycle doesn’t charm you; it’s purpose is to win, to dominate and to defeat. Racers, in that regard, are ruthless. Fragile egos covered in battle scars. Nobody knows more than a racer about extracting speed and agility from a motorcycle and that explains Ducati’s newest. The V4 S was never designed with appeasement in mind. No wonder it has that turned-up nose that, a few years ago, would have at least caused its designer’s citizenship to be revoked.

There’s no way trading timelessness for lap times can be a great idea, though. For all its extremities, the V4 S will soon be forgotten; these days, flagship superbikes evolve faster than you can say ‘Desmoquattro’ anyway. While Ducati Corse, the company’s formidable racing division, has displayed its aptitude in keeping up with this race nobody called for, the motorcycles that have been emerging from Borgo Panigale as a consequence aren’t quite tragic-eyed works of art anymore. Can there ever be another 916? No. Not unless the Vatican puts in a strong word, at least. Hey, isn’t there a new Pope in town?